John C. Harrison

For years, I used to bite through pencils in frustration, trying to come up with some logical explanation for the seemingly capricious nature of speech blocks.

— Why do I have good days and bad days?

— Why do I sometimes block on words I usually can say without effort?

— Why does the feeling that I’m going to block seem to come out of the blue and for no apparent reason?

— Why can I go along for three minutes without a block, and then suddenly have everything fall apart?

I used to think I’d be better off if I stuttered on every word, rather than only in special situations. At least then, my life would be more predictable. Non-stutterers have no idea of the uncertainties that are created when something as basic as your speech stops and starts and lurches like a car with carburetor problems. It casts an uncertain shadow on every aspect of your life.

I once tried to explain this mindset to a non-stuttering friend. Imagine, I said to him, that you’re walking merrily along the street after an uneventful shopping trip to Macy’s when all of a sudden this gloved hand comes out of nowhere and — WHUMP! — it bops you on the nose. Not hard. Not so it draws blood. But sudden enough to startle you.

“Hmph!” you say. “Now where did that come from?”

A bit ruffled, you continue on down the street. You walk into the bank to make a deposit. Just when you step up to teller window and open your mouth to speak, a gloved hand comes out of nowhere and — WHUMP! — it bops you on the nose. Not hard, but hard enough to disconcert you.

You make your deposit and leave the bank. Walking by a newsstand, you feel a bit rattled and decide to buy a magazine to take your mind off of your anxieties. You fish around for the right change, hand it to the man behind the counter, open your mouth to ask for the magazine…and suddenly this gloved hand comes out of nowhere and — WHUMP! — it bops you on the nose.

How is the world feeling right now?

Unpredictable.

It’s lunchtime, so you walk into a local eatery. As you walk through the door, you notice you’re doing something you didn’t do before. You’re scanning the room ahead of you, looking for that damned gloved hand. Your schnozz is tired of getting bopped. Except nothing happens. Reassured, you find an empty table, sit down, and open up the menu. Ah, the roast beef sandwich looks great. The waiter comes over to take your order.

“What would you like,” he says.

“The roast beef on whole wheat,” you answer.

“Anything on the side?”

“Yeah, an order of fries.”

“And to drink?”

“A Miller Lite.”

“What was that again”

“A….” You go to repeat Miller Lite, but you never make it, because suddenly a gloved hand comes out of nowhere and — WHUMP! — it bops you on the nose.

Oh stop it!!! Why is this happening? None of it makes any sense. Why could you buy a shirt in Macy’s without incident, and then walk into the restaurant and get bopped. This constant surprise is driving you crazy.

My friend said he now understood why I found the world so unpredictable.

Speech blocks have many triggers

Traditional thinking says that stuttering is all about what we do when we’re afraid we’re going to stutter. Speech pathologists and most PWS have professed this for almost 80 years. But like many explanations of stuttering, this is only a partial truth. A fear of stuttering can definitely cause more stuttering, and it also explains the self-reinforcing nature of the problem. But it certainly doesn’t explain what triggers all stuttering blocks. And it does nothing to explain the fact that stuttering can come and go at odd moments and often seems to have a mind of its own.

During my own recovery process, I identified many situations that had nothing to do with stuttering fears per se and yet were fully capable of triggering a speech block.

In this article, we’re going to set aside the familiar and obvious reasons why people block, most of which have to do with a fear of stuttering. Instead, we’re going to look for the less obvious causes that often play a key role in initiating a stuttering block.

But before we do that, there are several things we need to get clear about. First, I need to explain what I mean when I say “stuttering.” I’m not referring to bobulating, which is a coined word that describes the effortless, disfluent speech you hear when someone is uncertain, upset, confused, embarrassed, or discombobulated. I’m talking about speech that is blocked. The individual feels locked up and helpless to continue.

Next I need to define my understanding of what blocking in speech is all about. I have come to understand blocking/stuttering, not simply as a speech problem, but a system involving the entire person—an interactive system that’s comprised of at least six essential components: behaviors, emotions, perceptions, beliefs, intentions and physiological responses. This system can be visualized as a six-sided figure in which each point of the hexagon affects and is affected by all the other points.

Thus, it’s not any one thing that causes a speech block. It’s not just one’s beliefs…or emotions…or physiological make-up…or speech behaviors that lead the person to lock up and feel helpless and unable to speak. It is the dynamic interaction of all these six components that leads to struggled speech.

I also need to share my understanding of the way that emotions contribute to the speech block.

The emotion track

If you’ve ever seen a piece of 35mm movie film — the kind they use in a movie theater — you’ll notice one or several wiggly lines to the left out of the picture frame that are constantly varying in width, like a line on a drum on a seismograph that measures the intensity of earthquakes. This is the optical track that contains the sound for the movie. No matter what is going on, that optical track is always there. If there is no sound, the optical track is simply a straight line. But the track is always there.

Using this as a metaphor, imagine that every moment you’re awake, there is a similar “emotion track” running alongside that contains the underlying emotions associated with what is transpiring. Your brain is constantly processing data, experiences, meanings, etc. If you could somehow record the “emotion track,” you’d see it constantly expand and contract, depending on the feelings associated with the particular environment, what you were saying, who you were saying it to, what words you were using, what thoughts you were having, and how you were feeling at the time.

Having difficulty with a particular word like “for” may not be about that word in particular. It may have to do with what has come before that word, or what you anticipate might come after and the emotions that this moment are engendering.

If you’re resistant to experiencing those emotions, you’ll be inclined to hold them back (block) until the feelings drop to a manageable level.

Optical sound tracks

How does the emotion track function? Let us say George, a person who stutters, is in a meeting with Mr. Peters, his boss. George suddenly realizes he has another meeting coming up that he’d forgotten about, and he has to interrupt his boss to find out the time as he may have to cut this meeting short. (He also feels a bit incompetent because he absentmindedly left his watch home that day.)

Notice that George has little emotional charge on the words “excuse me.” But when he goes to say the word “Peters,” he has a short block, because his boss’ name has an emotional charge for him. That charge pushes his feelings beyond his comfort zone, prompting him to hold back for a moment until the intensity of those feelings drops. The block is indicated by the spike in the emotion track that indicates that George’s emotions have suddenly shot outside his comfort zone.

Now George has to deal with the hard consonant “c” in “can.” Not only has he had trouble with “c” in the past, but he has a fear that Mr. Peters will not like that he has to interrupt the meeting. This makes it even more difficult to let go. George’s feelings spike again on the “t” in “tell,” but they really spike on the “t” in “time.”

Why is that?

The word “time” not only begins with a feared constant, it also completes the thought. Once he says “time,” Mr. Peters will know that George has a time issue and wants to leave the meeting. In anticipation of Mr. Peters’ annoyance and how small and unloved that will make him feel, George blocks on the “t” and has to try three times before he can push the word out.

What’s amazing is that all this is going on, and George isn’t aware of any of it. But then, George isn’t aware of a lot of things. He isn’t aware of his feelings about authority figures, and how they intimidate him. He isn’t aware of his compulsion to please others and to make sure they always like him.

But most significant, George isn’t aware that his mind is programmed to constantly processes his experience, evaluating each moment to look for what may further his health and survival, and what might threaten it. In fact, neuro-linguistic programming (NLP) claims that we process over two million bits of information via our senses every second and that we delete, distort and generalize this information to “suit” ourselves. As motivational speaker Anthony Robbins says, “Everything you and I do, we do either out of our need to avoid pain or our desire to gain pleasure.” This probably sounds too simple, but virtually all life functions this way. It’s just that the complexity of the human mind tends to mask this basic drive.

There is never a time when you are without an emotion track. Sometimes, that track is quiescent, such as in moments of deep relaxation. But that track is always there to guide you away from those things that may cause you pain, and toward those things that are likely to give you pleasure.

This is what I have come to observe about the relation between emotions and speech blocks. Now let’s look at another key part of the puzzle: the way our experiences are stored.

The holistic nature of engrams

As I better understood the dynamics of the speech block and the strategies I employed to break through or avoid it, the behaviors I used to find so bizarre were no longer strange. But it was not until I stumbled across the concept of the engram that I found a credible explanation for the unpredictable nature of those damnable speech blocks.

The engram can be defined as a complete recording, down to the last accurate detail, of every perception present in an experienced moment — a kind of organic hologram that contains all the information derived from the five senses—sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch—as well as whatever thoughts arose at the moment. This cluster of related stimuli is imprinted on the tissue at the cellular level. Permanently fused into the body’s circuits, it behaves like a single entity.

Here’s an example of an engram. You’re in a shopping mall buying a pair of jeans when you suddenly hear a scream. You quickly look up and notice that a scruffy guy with long hair and a skull tatooed on the back of his left bicep and wearing a jeans jacket is holding a gun on the poor clerk at the checkout counter, and he’s demanding that she give him the contents of the cash register. Instantly, your heart starts racing The man grabs the cash from the girl and starts walking briskly toward you. In a panic, you wonder what to do. Should you run? Should you look away. Should you stand still? The man is now looking at you full in the face, as if daring you to challenge him. You instantly look away and hold your breath. He continues on and in a moment, he’s lost in the crowd. You give a big exhale. Behind you, the sales girl is hysterical.

Ten minutes later, you are providing an eyewitness account of the incident to the mall’s security police. You recall his estimated height and weight. You describe, as best you can, his tattoo and the kind of jeans jacket he was wearing. Perhaps you even had the presence of mind to notice his shoes and the color of his hair. But there were many other perceptions that you didn’t report, partly because they did not seem important and partly because you did not consciously notice them. These experiences were woven together into a single engram.

For example, there was a Mariah Carey song playing on the store’s audio system. If someone were to ask, you probably couldn’t recall this detail, but your subconscious mind recorded the song as part of the engram. When the robber walked past you, your olfactory senses picked up a whiff of motor oil from the spill on his pants. Your subconscious mind saw his rough complexion and the fact that he had a small scar at the very bottom of his chin. That was part of the engram, too. Your eyes recorded the harsh store lighting that radiated from transparent globes. Also part of the engram were the crowd noises from the mall, the emotional overtones of the clerk’s screams, the feel of the carpet under your feet, the tension in your legs and body, how thirsty you were. And of course, there were all your emotional reactions—the fear, panic, shallow breathing, tightness in your neck, the cramp in your stomach. All these perceptions and more were recorded and organized into an engram.

Why is all this important? It’s important because the engram plays an important role in your body/mind’s survival strategy, especially in its relation to a little almond-shaped node within your brain that represents the seat of your emotional memory.

The amygdala

This node is called the amygdala and is located within the limbic system, the most primitive part of the brain that has elements dating back several hundred million years. It’s function is reactive—designed to quickly trigger a fight-or-flight reaction whenever the organism (you) feels threatened.

The amygdala has connections, not just to the autonomic nervous system, which controls physiological reflexes such as your heart and breathing rates, but also to other brain regions that process sensory input. It has a special high-speed pathway to the eyes and ears that give it access to raw and unprocessed sensory information. It’s like a neural hub with a trip wire that’s primed to fire whenever danger arises. In short, the amygdala is designed to by-pass the higher, conscious brain that controls cognitive processing so we can act first and think later.

Thus, when we perceive a threat, our body initiates a rapid fire sequence of events, comprising both a fear response and an instant reflex to pull back from whatever we’re doing that triggers that fear.

The problem is, the amygdala is not very smart or discerning and doesn’t differentiate between physical threats (tigers, robbers, fires) and social threats. When any kind of a threat is perceived, the amygdala interprets it as an issue of physical survival. It triggers the sympathetic nervous system, and all at once your breathing becomes shallow, your blood pressure rises, blood rushes to your limbs, heartbeat increases, adrenaline rushes into your blood — a reaction that is designed to give you the physical resources to challenge the threat or run from it.

How does your amygdala know when to trigger a reaction?

It triggers it when there is some element within the moment that suggests the situation is threatening.

Thus, a month later you’re in a bookstore and suddenly find yourself feeling uneasy. What you’re not aware of is that Mariah Carey has just started singing the same tune over the audio system. This one sensory experience recalls the entire jeans shop event. Yet, you’re not consciously aware of this. You just know that your heart is beginning to race.

Later that week you’re on a bus and you suddenly become uneasy. What you don’t realize is that the guy seated next to you works in a garage, and you’re picking up the same scent of motor oil that you experienced in the jeans shop.

In the fast-food restaurant the guy behind you has a tattoo on his shoulder. You feel yourself holding back.

Several days later you walk into a clothing store that has the same harsh lighting as the jeans shop, and suddenly you find yourself edgy without knowing why.

A person you’re talking to at work asks you a question. His voice has the same timber and quality as the robber’s, and as you respond, you find yourself wanting to hold back.

Notice that your circumstances are vastly different from the day you witnessed the robbery. You’re in a McDonalds, not a jeans shop. The guy with the tattoo is there to eat a hamburger, not rob the store. And yet, your emotions are doing a number on you. The reason has to do with how your reactive mind operates. In short, anything that looks like or feels like or even vaguely reminds you of the original experience has the ability to recall and recreate the original experience.

The scruffy guy is the hold-up. The scent of motor oil is the hold-up. The Mariah Carey record is the hold-up. The harsh lighting is the hold-up. The co-workers voice is the hold-up. Each sensory cue functions as if it were a minute piece of a hologram. Shine a strong beam of light on that one little piece of a hologram, and you can see the entire event. Similarly, the most “inconsequential” sensory experiences have the power to recall the entire engram and the emotional responses attached to it.

In the case of speech blocks, a fear of blocking is the most obvious trigger that can cause a person to lock up and be unable to speak. But there are many more ways to trigger this same response. Let’s look at some of the non-stuttering-related circumstances that can trigger a stuttering block.

Reacting to a tone of voice

One trigger is an individual’s tone of voice. Delancey Street Foundation in San Francisco is in the business of rehabilitating drug addicts, prostitutes, convicted felons, and others with acting out character disorders, and they are more successful at it than any other organization in the world. Over a 30-year span, I’ve periodically donated my services to Delancey as an advertising copywriter and have supported them in other ways.

In 1993, I volunteered to teach a public speaking class at Delancey. One day after the class was concluded, I was on my way to my car when I decided to drop by the Delancey Street restaurant located in the same building to say hi to Abe, the maitre d’, whom I had known for 20 years. I didn’t see Abe when I walked in, so I asked the acting maitre d’ to tell Abe that John Harrison had stopped by and asked for him.

I turned to leave when suddenly the fellow I’d just spoken to abruptly called out, “What’d ya say ya name was?”

I turned back to give him my name again, and suddenly I found myself blocked. More specifically, I was in a panic state, frozen and unable to say a word.

Totally flustered, my head swirling, I was catapulted back 30 years to when I used to regularly block in situations like this. Feeling totally self-conscious, I stopped, took a deep breath, and finally was able to bring myself back to “consciousness” so that I could say “John Harrison.”

I left the restaurant upset and puzzled by the sudden appearance of an old reaction. Why did it happen? I’d had a wonderful class. I love Delancey Street—both the people and the organization. This was our favorite restaurant in San Francisco. I wasn’t thinking about my speech; that had stopped being an issue over two decades ago.

The more I thought about it, the more I felt there was something in the fellow’s tone of voice that had triggered my response.

This is precisely how an engram works. It’s not necessarily the situation that triggers you, but some part of the situation that recalls an older event that was threatening in some way. Perhaps it had been a similar situation in which I’d blocked. Or perhaps there was something about the fellow himself. After all, almost all of the residents in Delancey had been in prison. Almost any of the guys could sound tough. Maybe I was intimidated by his tone of voice. He may have barked the question because he saw me leaving and realized that he hadn’t properly heard my name. Maybe that caused him to panic, and maybe I interpreted that panic as something else. A threat? A command? His tone did catch me off guard. Or perhaps there was something about my mindset that day that simply made me more susceptible to his tone of voice. I’ll never know. But I do know that for an instant, I was reliving an incident from an earlier time and place.

Single incidents like this only happened every few years. But when they did, they provided a quasi-laboratory setting to study the circumstances leading to a stuttering block.

The big difference between my response that night and how I would have responded 25 years ago is that, once the event was over, it was over. Though I was curious about it, I didn’t brood about it. Nor did I see it as a problem with my speech, so it did not reawaken any speech fears. It was just one of those things that occasionally comes out of the blue.

This story is just one example of how a situation not involving a stuttering fear per se can suddenly cause a shift in one’s “hexagon” and trigger a speech block.

Reliving a familiar scenario

Now let’s go back even further. By the late 1970’s I had been free of speech blocks for more than a decade, although every several years I would be surprised by an isolated incident. Like the Delancey Street encounter, these moments happened so infrequently that they gave me a laboratory-like opportunity to examine under a mental microscope the inner workings of the block.

This particular episode took place at Litronix, a manufacturer of light emitting diodes in Cupertino, California. I was the advertising writer on the account, and I and Bob Schweitzer, the account executive from the advertising agency, were at the company to present text and layout for a new ad.

Our appointment was for 10 a.m., but since we were a few minutes early, we found ourselves hanging out in the doorway to the office of Litronix president, Bruce Blakken, while he completed a phone call. As I stood chatting with Bob, I suddenly found myself feeling uneasy about introducing myself to Blakken, whom I had not previously met. I had the old familiar feeling that I would block on my name.

That was crazy. I hadn’t dealt with speech blocks in a dozen years. I never thought about stuttering in these situations. Why was this feeling making an unexpected reprise? The closer Blakken seemed to be to completing his phone conversation, the more I found myself worrying about my introduction. Eventually Blakken finished his call and motioned us in. Bob shook hands and immediately introduced me, avoiding the need for my having to say my name. Could I have said it without locking up? I would like to think so, but at the moment, I wasn’t sure. I only knew that I was off the hook.

Later that evening I sat down at home and mulled over the experience. What was going on at Litronix? Where did those feelings come from, and why did they show up at that particular moment?

I kept turning over the incident in my mind, looking at various parts of the tableau in an effort to find a clue that would explain my reaction. Eventually, something began to jell.

Two decades previously I had worked for my father in New York City. Our ad agency was housed in a small four story building on 50th Street where I worked downstairs. My father’s office was on the third floor, and sometimes I would go up to his office when he was on the phone. Unlike visitors from the outside who had to follow a formal protocol (receptionist, waiting room, secretary, and then be ushered in), I’d just hang out in his doorway until he finished his call. After all, I worked there, and besides, I was his son. I could take liberties.

The incident that day at Litronix felt remarkably similar. Because the company was informal, there were no official protocols to follow. We had waited in the reception area before being escorted to Blakken’s office, but after the young woman escorted us down the hallway, she simply said, “Oh, he’ll be done in a minute, and left us standing in the doorway.”

I had been here before. My emotional memory did not acknowledge the differences; rather, it responded to the similarities—head of company, standing in doorway, need for approval, attitudes about authority. These were pieces of a familiar engram that recalled the times when I waited for my dad to get off the phone. Not only did it recall the earlier experience, it became the earlier experience. He was my dad. I was his son, worrying that he wouldn’t approve of what I had done. And consequently, all the old feelings came back. These, in turn, brought back attitudes and feelings I had as a young man, including those about being judged and having to perform.

My amygdala, charged with protecting me from bodily harm, had made another mistake. Once again, it had inappropriately set off my general arousal syndrome to get me ready to fight or flee the saber-tooth tiger.

Fear of having your ideas rejected

A third type of fear-of-blocking scenario involves speaking to teachers, employers, or anyone who we cast in a higher position because of what they know, what they do, or what they can do for or to us. I used to think it was always because I might stutter in front of them. Now I know better. Fear of stuttering can be a valid fear. But fear of having my ideas rejected, something I took very personally in those days, can be equally intimidating, even if you no longer deal with stuttering.

In the mid-90s I was in a workshop sponsored by the Northern California Chapter of the National Speakers Association. Mariana Nunes, who taught the class, was a wonderful, supportive person and an accomplished professional speaker.

Among the subjects she addressed in the workshop was the need for an effective speech title. I had a talk that I’d given to local community organizations, and at the time, it was entitled, “Is It Fun, or Is It Work?” The talk was about how we tend to separate work and fun and how to build a relationship with work in which work and fun can become synonymous. Mariana felt my title would leave people unclear about the nature of my speech. I liked the title and was resistant to changing it. She said that during the workshop we’d have a chance to try out our speech titles on the other members of the group.

She was half way through the workshop when she asked if anyone had a speech title they’d like to test. At first, I did NOT raise my hand. Other people tried out their speech titles, but I held back. I should also mention that virtually all the people in the workshop were either professional speakers or wannabe speakers, so the caliber of those attending was high. I felt intimidated. Offering my speech title to this group meant that I would be judged by those whose opinion I held in high esteem. I had a fear of having my title rejected. But I didn’t want to feel rejected, so I kept holding back.

Eventually, I did raise my hand, but when I did, an old familiar feeling enveloped me. I felt like I was going to block. Now, at that time I hadn’t dealt with chronic speech blocks for over 25 years, although every once in a while, a situation would arise that brought up the old feelings. Though I felt as if I would block, I was also aware that it had nothing to do with my speech. It had to do with my divided intention. I sort of wanted to offer my speech title, but at the same time, I didn’t want to make myself vulnerable to the judgments of others. So I really DIDN’T want to speak. This pull in two different directions was creating a familiar sensation that I would lock up and not be able to talk.

I’d like to say that I ignored my feelings and spoke up, but I am embarrassed to admit that I finally put my hand down, and never did share my speech title. I felt bad about it afterward. However, once again, I was aware that the issue wasn’t about stuttering. It was about making myself vulnerable.

Fortunately, I had a second chance two months later when Mariana held another workshop. Once again, there was an opportunity to share speech titles. This time, my intention was clear, and mine was the second hand that shot up. When I did share the title, the words just flowed. I even felt surprised that it was so easy. As you can see, my mindset was totally different because my intentions were clear, aligned, and focused.

Had I only focused on my fear of stuttering the first time around, I would never have broadened my purview to include all the other issues that were involved. I would have reinforced the belief that I had a speech problem, and that it was a fear of stuttering that was keeping me back. I would have overlooked the real issues.

By the way, Mariana was right. They didn’t like the title. It wasn’t communicating. (I survived that revelation.) My presentation is now entitled, “Why Can’t Work Be More Fun?” and organizations are much clearer about the nature of the speech.

Talking to an unresponsive listener

A fourth situation in which a fear of blocking may have nothing to do with fear of speaking occurs when we speak to a totally unresponsive listener. The person just sits there, stone faced. Brrrrrr. Even now, that’s a tough one for me. I’m getting absolutely no clues to how I’m being received.

The need to be heard is one of the most powerful motivating forces in human nature. It has enormous bearing upon our development throughout childhood. Being listened to is the means through which we discover ourselves as understandable and acceptable…or not. It spells the difference between being accepted or isolated.

This also makes not being understood one of the most painful human experiences. When we’re not appreciated and responded to, our vitality is depleted, and we feel less alive. We are also likely to shut down.

Talking to an unresponsive listener is a lot like looking into a pitch black room. We project our own boogiemen into the darkness. In the absence of a response, our insecurities are awakened, and questions start undermining our self-esteem. Are we making sense? Are we well-regarded? Or are we being seen as the total fool, acting stupid and prattling on and on.

These questions wouldn’t be so important if we didn’t give the listener such power over us—the power to validate us, to tell us we’re okay.

Why don’t we just validate ourselves? Why do we need them? Because we create our own feelings of low self-esteem, and then turn to the other person to make us feel okay.

They have power over us because we want something from them—approval, love, acceptance. Sometimes, they’re in a position to dole it out because of their position. But often, it’s simply that we make them important and then look to them to validate us.

Our fear, of course, is that they’ll do just the opposite. They won’t like us or want us. So we desperately try to become presentable. We hold back our unworthy self. We second guess what they want, so we can provide it, or be it. We hide our dysfluent speech…our assertiveness…our spontaneity…our real self. Careful! Something may come up that the other person will find offensive. Because of their sphinx-like, expressionless manner, we tread lightly around them, as carefully as if we were walking on broken glass. We do everything we can to make ourselves liked. And when they don’t react, we hold back even more.

Our ultimate fear? It’s that they will abandon us. I call it the ultimate fear, because in our child-like state, if we’re helpless and abandoned, it means that we may die.

No wonder I grew up obsessed with always having to know whether I was coming across and whether people were receptive to what I had to say. I constantly looked for non-verbal clues to tell me whether or not I was connecting—a smile, a look of interest, an attentiveness.

But some people are just not expressive. It’s not that they don’t like you or don’t appreciate what you’re saying. It’s just not in their nature to be responsive.

I’d like to tell you I’ve outgrown all this, but the fact is that unresponsive people still make me uncomfortable. It has nothing to with a fear of stuttering. It has to do with a fear of not being validated, and 30 years ago in these situations, I would be highly likely to block.

The Alarm Clock Effect

A participant on the Internet’s neuro-semantics discussion group raised an interesting question. He asked, “If a person blocks to hold back and to avoid experiencing an emotion, etc., how does that relate to neutral, meaningless words such as ‘the’ and ‘and,’ as opposed to words with real content.”

One explanation for why we sometimes block on “meaningless” words is something I call “The Alarm Clock Effect.” This has nothing to do with a fear of stuttering per se, but about feeling that we’ve been speaking too long. We’ve been acting too assertively, and now it’s time for us to pull back.

When I first came to San Francisco years ago and joined the Junior Advertising Club, I periodically had to get up and speak in front of the group. On these occasions, I noticed an interesting phenomenon. In the beginning, I could speak for about 10 seconds before my “alarm clock” went off, and my anxiety level climbed to an uncomfortable level that would cause me to block. This had to do with my level of comfort in the situation and how long I could tolerate being in the power position (i.e.: in front of the group) before my feelings zoomed outside my comfort zone. Thus, I might block on the word “for,” not because that word was threatening, but simply because I had been letting go in front of the group for too long, and now I felt compelled to rein myself in. (A related fear is when someone speaks “too long” in a performance situation without blocking and the self-imposed pressure to keep up this perfect performance becomes overwhelming.)

However, the more opportunities I had to be up in front of the group, the more ordinary it began to feel, the more comfortable I became in the situation, and the longer I’d be able to speak—30 seconds, 45 seconds, one minute—before my alarm clock “rang.” This was an indication of my gradually expanding comfort zone as well as my growing willingness to assert myself.

As your self-esteem grows, as you build confidence in your ability to express yourself and become increasingly comfortable with projecting your power, you’ll find yourself able to speak for longer and longer periods without constantly hitting the brake. Speaking will cease to be an activity that wears you down; rather, speaking will energize you as you release more and more energy, because you are no longer working against yourself. Your “alarm clock” will allow you to go for longer periods without “ringing,” and eventually, may stop ringing altogether.

In analyzing a speaking situation, get in the habit of noticing what your emotions are doing and whether, just before you blocked, your feelings moved outside your comfort zone, causing you to pull back. Then ask yourself what the threat was. You can speed up the learning process by keeping a diary or writing down the incidents you remember on file cards. If you do this over time, you’ll begin to see definite trends and patterns. And those, in turn, will identify problem areas that need to be addressed.

How about people who seem to block in all situations?

After more than 26 years with the National Stuttering Association, I’ve seen every kind of stuttering you can imagine. I’ve met people who only block occasionally, and I’ve met those who struggle with every word.

What accounts for the people who seem to stutter all the time?

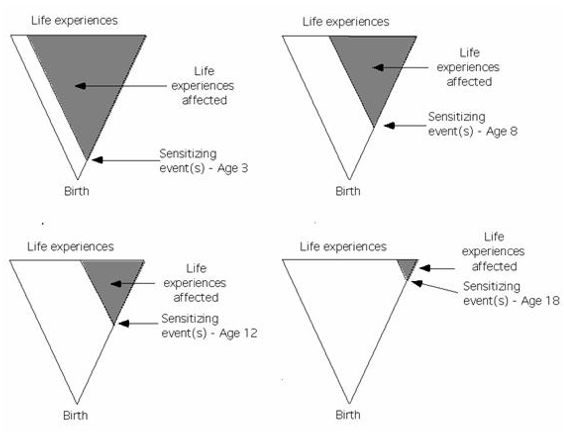

To help explain this, I devised something I call, “The Principle of the Upside Down Triangle.” This metaphor refers to the time in the child’s life at which particular sensitizing events take place. The earlier they occur, the broader the impact they will have on the person’s life later on.

Let’s say an 18-year old speaks up in class and is severely criticized and humiliated by a male teacher. There is the likelihood that the student will develop a fear of that teacher, or similar male teachers, and be discouraged from contributing further in that class.

If the event takes place at age 12, the student may not be as discerning and may project that fear onto all teachers.

If it happens at age eight, he may end up being afraid of all adults.

If it happens at age three, his fear may become generalized, not only to adults, but to any situation in which he’s called upon to be assertive.

At age three, he is not so much relating to the shoulds and should-nots of specific situations as he is to whether certain emotions are safe to express at any time.

For example, assertive feelings are an integral part of sex, creativity, and the expression of anger, hate, tenderness, and love. They’re part of one’s ego. If early in the child’s formative years he is put down for expressing his wants or needs in any of these activities, his fear of expressing strong feelings can easily become generalized.

He may come to the conclusion that his true self should never be revealed under any circumstances. Self-assertion per se may become a no-no. Then, almost all speaking situations will be threatening, and he’ll find it difficult to speak anytime, anywhere, without blocking.

Similarly, if not being listened to commences during early childhood, this would also have a broader impact on the individual’s life.

Compare this to the individual who’s sensitizing experiences occurred later, and whose fears are generally limited to specific situations.

As you can see in the above diagrams, the earlier the sensitizing events take place, the broader the impact they will have on an individual’s life, and the more widespread will be the incidence of speech blocks.

Imprinting the brain

Changes are also more difficult to implement when the unwanted behaviors are acquired early in life. An article in Time magazine in February 1997 explains why. The article starts out by describing how neural circuits are established:

- An embryo’s brain produces many more neurons, or nerve cells, than it needs, then eliminates the excess.

- The surviving neurons spin out axons, the long-distance transmission lines of the nervous system. At their ends, the axons spin out multiple branches that temporarily connect with many targets.

- Spontaneous bursts of electrical activity strengthen some of these connections, while others (the connections that are not reinforced by activity) atrophy.

- After birth, the brain experiences a second growth spurt, as the axons (which send signals) and dendrites (which receive them) explode with new connections. Electrical activity, triggered by a flood of sensory experiences, fine-tunes the brain’s circuitry—determining which connections will be retained and which will be pruned. [My emphasis]

The article observes that “by the age of three, a child who is neglected or abused bears marks that, if not indelible, are exceedingly difficult to erase.”

That would also be true of children who are subjected to anxieties about self-expression and who develop strategies and patterned behaviors designed to help them cope.

Then, from later in the article: “What wires a child’s brain, say neuroscientists…is repeated experience. Each time a baby tries to touch a tantalizing object or gazes intently at a face or listens to a lullaby, tiny bursts of electricity shoot through the brain, knitting neurons into circuits as well defined as those etched onto silicon chips.”

This process continues until about the age of 10 “when the balance between synapse creation and atrophy abruptly shifts. Over the next several years, the brain will ruthlessly destroy its weakest synapses, preserving only those that have been magically transformed by experience.”

No wonder some people have such overpowering difficulties with speech. Through repetition, their early fears of self-expression, with all the attendant perceptions, beliefs, and response strategies, have become deeply etched in mind and body and incorporated as part of the individual’s personality. In a similar manner, the blocking strategies they adopt also become habituated.

Can early programming be defeated?

The good news is that you can reformat these early experiences by reframing them so that the old reactions are not called up. You can also provide yourself with a choice of responses by developing new behavior patterns and repeating them over and over again until you automatically default to them. You will have to work much harder at creating those new response patterns, because your mind is no longer a blank slate and a certain amount of unlearning is now required. You will also have to address much more than your speech. You’ll have to address the perceptions, beliefs, emotional responses, and conflicting intentions that help to create the reactive patterns leading to a block.

Can it be done?

Yes, says author Daniel Goleman. In his book, Emotional Intelligence, Goleman talks about a problem that, like chronic stuttering, usually starts in one’s early years: obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). He reports that those being treated for OCD, which is another hard-to-break and deep-seated disorder, have been able to change their feelings and responses. They do it by confronting their fears, examining their beliefs and generating repeated experiences of a positive nature.

For example, one of the more common compulsions of the OCD sufferer is repeated hand washing. People are known to wash their hands hundreds and hundreds of times a day, driven by a fear that if they failed to do this, they would attract a disease and die. During therapy, patients in this study were systemically placed at a sink but not allowed to wash. At the same time, they were encouraged to question their fears and challenge their deep-seated beliefs. Gradually, after months of similar sessions, the compulsions faded.

Repeated positive experiences did not eradicate the old memories. They still existed. But it gave the individuals different ways of interpreting them and alternative ways to respond. They weren’t stuck playing out “the same old tune.” True, it took more effort to counteract the old responses whose roots reached back to early childhood. But motivated individuals were able to disrupt the old reaction patterns and relieve their symptoms, as effectively as if they had been treated with heavy-duty drugs like Prozac.

Says Goleman, “The brain remains plastic throughout life, though not to the spectacular extent seen in childhood. All learning implies a change in the brain, a strengthening of synaptic connection. The brain changes in the patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder show that emotional habits are malleable throughout life, with some sustained effort, even at the neural level. What happens with the brain…is an analog of the effects all repeated or intense emotional experiences bring, for better or for worse.”

The same principle applies to chronic speech blocks.

By venturing outside your comfort zone, being willing to experience your way through the negative emotions, and by reframing the old learnings using Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP), Neuro-Semantics® and other tools from cognitive psychology—you can build alternative responses, even though the old memories will always exist in your emotional archives. The adage, “What doesn’t kill you will make you stronger” really applies.

But to effect these changes, you have to put yourself at risk (at least, in your own mind) by such things as disclosing to people that you stutter, deliberately looking for speaking opportunities, and finding regular opportunities to speak, especially in those situations that feel risky but are actually safe, such as Toastmasters.

Such repeated risk-taking activities affect, not just your speech, but your total self. They reprogram your emotional memory. They help you create a broader, more honest and grounded sense of who you are by building positive beliefs, perceptions, and emotions. In effect, you’re changing, not just your blocking behaviors, but the whole ground of being that supports those behaviors. By giving your Stuttering Hexagon a more positive spin, you are assuring that the old ways of holding back and blocking will no longer be appropriate for the newer, expanded, more resourceful you.

Keep looking at the big picture

I have to confess I’m really frustrated when, year in and year out, people maintain their tunnel vision about stuttering. For years and years, people were mystified by their speech blocks. Nobody knew what they were about. Then along came the speech clinicians and researchers who offered a simple and logical explanation: “Stuttering is what you do to keep yourself from stuttering.”

The world hungrily claimed this as The Explanation. “Hurray!” said everyone. “We now have an answer that makes sense.”

That’s when the blinders went on. People stopped looking. We assumed that this explanation was the entire answer. We limited our perspective. We stopped questioning whether there were other parts of the problem that had to be factored in.

Fortunately, not everyone has fallen into that trap. I’ve met many individuals who have substantially, or fully, recovered from stuttering, and all of them looked beyond the obvious. They developed a keen awareness of themselves as people. They made an effort to notice how they thought and felt, and they correlated those actions and experiences with their ability to speak.

Ultimately, they came to understand that underlying their speech blocks was a need to hold back, and that the reasons for holding back were linked to many facets of their life, not just to a fear of stuttering. The self-knowledge they developed became an integral part of their recovery.

If you’re one of those individuals for whom constant practice of speech controls is not working…or if the effort to remain fluent has become too difficult…perhaps it’s not because you haven’t been practicing hard enough. Maybe it’s because you haven’t established a Fluency Hexagon to support the fluency goals you’re working toward. Your hexagon is still organized around holding back, rather than letting go.

If that’s the case, it’s time to broaden your field of vision. It’s time to look beyond your fear of stuttering and start discovering the ways your speech blocks are intimately connected to all the various aspects of who you are.

REFERENCES

Nash, J. Madeleine. (1997) Fertile minds from birth, a baby’s brain cells proliferate wildly, making connects that may shape a lifetime of experience. The first three years are critical. Time, 00:55, 47-56.

Robbins, Anthony. (1991) Awaken the Giant Within. New York: Simon & Schuster, 53.

Goleman, Daniel. (1995) Emotional Intelligence. New York: Bantam Books, 225-227.