by Tim Mackesey, CCC-SLP

Pour la traduction française, cliquez ici (PDF)

Purpose

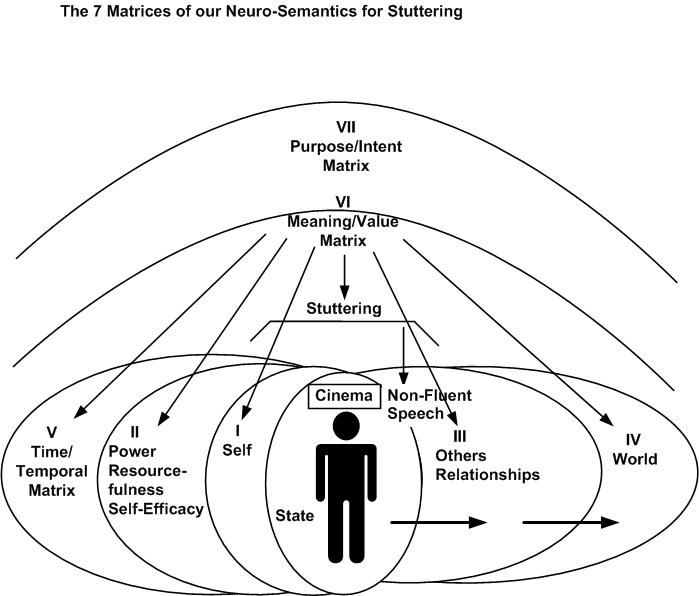

The intention of the State Management Graph below is to help people using Neuro-Semantics to habituate the use of strategies. Daily use of strategies will provide for more consistent resourcefulness and improved fluency. To make sense out of the acronyms and terminology in the graph, a background in Neuro-Semantics is required. Many of these strategies are available for free as downloads from www.neurosemantics.com. Others are outlined in Bob Bodenhamer’s training manual, Mastering Blocking & Stuttering: A Handbook for Gaining Fluency, available on-line through the website.

What is a state and why is important to me to manage mine? A simplified definition of a state is how resourceful you are feeling and thinking at a given moment. In the body of a person who stutters (pws), a state can be measured by rate of breathing, degree of muscular tension (particularly in the torso, larynx, tongue, and lips), energy level, blocking, rate of speech, and many other dynamics. In the mind of a pws, a state can be evaluated by terms such as mood, feeling safe or threatened, anticipatory anxiety, confidence, beliefs about listener’s reaction, and other cognitive-linguistic phenomenon. If you manage your state, you run your brain; and vice versa.

PWS, like all other human beings, are at-risk for embarking on personal change and then becoming complacent or “forgetting” to do the very strategies they know help them. Do you know anyone who announced a “New Year’s Resolution” and did not achieve it?

Someone once coined the expression that is takes 21 days to form a new habit. By using the graph and holding yourself accountable you will form new habits. To succeed a person must have a compelling future image of what it will be like to have freedom of speech, specific strategies, beliefs to support success, a strong purpose for achieving it, and then make a decision to DO IT.

Towards Motivation

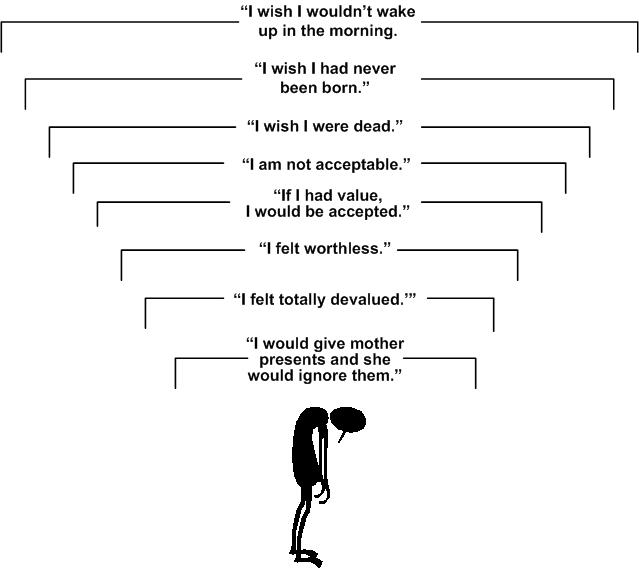

Towards Motivation occurs when we are driven to achieve a compelling outcome. An outcome must have significant meaning to us. When this propulsion system is programmed into your mind, it works like a guided missile. Every pws I coach comes to me with “away from motivation.” They are trying to not stutter. They have, in effect, developed a propulsion system programmed to prevent and avoid stuttering. This missile will miss the target. Below is an example of away from patterns common to pws:

( – ) ( +)

AWAY FROM STUTTERING TOWARD FLUENCY

<——————————————————————————————————————–>

– word changing

– avoiding talking

– eye contact aversion

– telephone avoidance tricks

– blocking

– mind-reading listeners

– interjections and filler words

– other attempts to conceal stuttering

–

Obviously, the pws must abandon each of these toxic, away-from patterns listed above if they desire to change.

Taking the concept of towards motivation and making it your propulsion system is critical to state management and eventual consistency in speech. Cognitive psychologist L. Michael Hall, coined the term mind-to-muscle (Hall, 2000) to describe how we take a principle and make it a daily habit. The graph is designed to help mind-to-muscle the use of the strategies. A pws can analyze his state, select a strategy, create a more resourceful state, and keep a score card by the graph.

How is that an obese person can dramatically change his entire being by sticking to an exercise regimen, changing his entire diet, and becoming disciplined? They must have propulsion system. A person who loses weight, and keeps the weight off, is motivated by either pain or pleasure. Pain can originate from a doctor scaring them with suggestions of future health trouble. Pleasure can come from making an image of themselves at their ideal weight. Whether the motivation for weight loss originated as a toward or an away-from pattern the successful dieter had to mind-to-muscle significant exercise and eating habits. These changes become a new “operating system.”

People who stutter know how to stutter very well. What I mean by this is that they have repeated patterns of thinking, feeling, and stuttering for years. When they begin to relapse the vortex opens and sucks them in. I stuttered severely well into my 20’s. If I was making gains for several weeks or months, it would take one incident of embarrassment about my stuttering to set it all off. It was like a computer program that was saved on my hard-drive (my brain) would open and run automatically. No matter how terrible I would feel about my stuttering, or how severely I would start blocking, it seemed so familiar and I felt helpless to it. I would start avoiding and fearing the relapse. I would slip right into the away-from patterns listed above. I eventually learned strategies from the domain of cognitive psychology to handle this roller coaster.

Eventually, a pws can learn to use strategies to prevent going into the stuttering state. Breaking out of the stuttering immediately is critical

To preventing relapse and regaining a resourceful state. Most of the strategies can be used before, during, or after talking depending on the intention. For example, the Drop-Down Through, Fifth Position, Foreground/Backgound, and others can be used in four different scenarios: 1) as a future pacing process early in the morning to manifest a resourceful speaking day, 2) when anticipating stuttering to remove anxiety, 3) during a speaking moment to relax and manifest fluency, 4) to re-imprint a moment of stuttering that the pws disliked. I personally believe that re-imprinting past stutters is critical to remove time-line references that will in-turn reduce or eliminate anticipatory anxiety. The table below offers a pws a practical resource to help habituate the use of strategies.

Get Started

Print off a minimum of 60-90 copies of the graph. Plan on devoting 2-3 months in order to mind-to-muscle these strategies. Take a 3-hole punch and put the graphs in a 3-ring notebook. Review the neurosemantic strategies and get started. Become active in the on-line discussion group for support and “pointers.” Like all other self-improvement endeavors, some people may benefit from a personal coach. Assess your “state” first thing in the morning. If unresourceful and/or anticipating stuttering, pick a strategy and do it. Mark the acronym on the graph and reassess your state (-10 to +10). I highly recommend an early morning future pace strategy such as the meta-alignment. As you move through the day take inventory of your state and use strategies as necessary. Remember that it is essential to break state immediately after discovering a pre-stutter state or noting any negative thoughts or feelings after a stutter. How do you know if a stuttering event warrants re-imprinting? If when you begin to “run a movie” about it and actually feel discomfort, re-imprint right away.

Caveat: You may become so good at running your brain that you manifest numerous wonderful things in your life. If abundance, fluency, and feeling great scares you, discard this road map.

References

Hall, L. Michael. (2000). Secrets of Personal Mastery. United Kingdom: Crown House Publishing

DAILY STATE MANAGEMENT

STRATEGIES

The following table contains a list of strategies and their acronyms.

ACRONYM TERM5P = 5th Position DDT = Drop Down Through EFT = Emotional Freedom Therapy FG = Foreground/Background FP = Future Pace |

ACRONYMTERMMA = Meta-Alignment MQ = Miracle Question MYN = Meta Yes/ Meta No PT = Phobia Theater RF = Reframing Self |

ACRONYMTERMKDD = Kinesthetic Drop DownTLR = Timeline Re-Imprint SWP = Swish Pattern GI = Guided Imagery |

AWARENESS STATE

Enter the appropriate strategy acronym in the box that corresponds to your awareness state at a particular time.

| +10 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| +9 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| +8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| +7 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| +6 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| +5 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| +4 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| +3 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| +2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| +1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| -1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| -2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| -3 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| -4 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| -5 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| -6 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| -7 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| -8 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| -9 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| -10 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 5AM | 6AM | 7AM | 8AM | 9AM | 10AM | 11AM | NOON | 1PM | 2PM | 3PM | 4PM | 5PM | 6PM | 7PM | 8PM | 9PM | 10PM | 11PM | MID- NIGHT |