Audio interview with Chazzler DiCyprian and John Harrison

Articles by John Harrison

How We Developed An Incorrect Picture of Stuttering

This is a slightly edited version of a keynote presentation by John C. Harrison delivered at the 2004 World Congress for People Who Stutter, held in Freemantle, Western Australia on February 15 – 20, 2004.

(Begin with stuttering demonstration)

There was a time when I was so petrified by having a moment that was not filled by words that I would sooner die than stand up here and be silent. I’m pleased to say those days are long past. I can’t think of anything more fun or more fulfilling than standing in front of an audience and feeling like I have something worthwhile to say.

The stuttering you saw a moment ago is indicative of how I would have spoken if you were my high school class, and I was up in front of you giving an oral report. My disfluencies began when I was three and my speech blocks started appearing a few years after that.

Unlike those who stutter most of the time, my stuttering was very situational. I could talk just fine when I was in the schoolyard chatting with my friends or playing football. But when I had to talk to the very same people in a classroom…or when I had to talk to an authority figure…or stop a stranger on the street to ask a question…or go to the market and ask for a container of milk…or get on a bus and ask for a transfer…I almost always had periods when I would lock up and not be able to speak.

So I know a lot about stuttering from the inside. I dealt with it until I was about 30 years old. And as a member of the National Stuttering Association for over 27 years, I’ve been intimately involved in all aspects of the stuttering community.

My participation in the NSA has given me exposure to a huge stuttering population. Not only did I function as the Associate Director for 14 years, I also participated in meetings of the San Francisco chapter for over a decade. And I was editor of the NSA newsletter, Letting GO, for nine years.

I’ve also conducted workshops all over the U.S. for people who stutter. And I’ve run workshops in Canada, Ireland, the U.K. and Australia.

Over the last 15 years, I’ve had extended correspondence on the Internet with literally thousands of stutterers around the world. I’ve taped scores of interviews. I mentor people on the net from many countries. I do coaching sessions over the phone. And I’ve followed people’s lives, some for as long as three decades. All this has been quite a learning experience. It has also validated the conclusion I came to almost 35 years ago…that for all the years we’ve been trying to understand stuttering, we’ve been using the wrong paradigm or model. We have incorrectly characterized what stuttering is all about.

But first, how many people are good at math? Okay, I have a little puzzle for you. These numbers are in this order for a particular reason. Can you tell me why they are in this sequence?

8…5…4…9…1…7…6…3…2…0.

Take about five minutes or so and see if you can solve it.

(Really take five minutes! And don’t cheat. Remember, you’re being watched.)

Figured it out?

Many of you could spend a week trying to solve this puzzle (as I did) and still not find the answer.

Why is that?

Let me ask you — did I make it easier or harder for you to solve?

Harder, you say? Why is that?

Oh, you’re telling me I led you astray. I got you thinking along mathematical lines when I asked, “How many of you are good at math? I got you to use the wrong paradigm.

I’ll cop to it. That’s just what I did. And you went for it.

Do you know what a paradigm is? A paradigm is a filter through which we look at the world. A paradigm tells us what’s important to pay attention to…and what’s not. It’s the way we frame reality.

For example in governance, a democracy would be one kind of political paradigm. A dictatorship would be another. Communism would be a third. There’s also a monarchy, oligarchy, socialism, and so on. Each paradigm shapes how you look at governing people. Thus a crowd gathered in the square might be perceived by the head of state very different, depending on whether he was looking at it through the filter of a democracy, dictatorship, or another kind of political paradigm (filter).

In order to find the answer to the number puzzle, you had to approach it from within an entirely different paradigm. You had to drop the idea that this was a numerical puzzle and think outside the box.

If you still haven’t figured it out, flip forward to end of the article for the answer.

So what can we conclude from this? We can conclude that if you don’t use the right paradigm, the problem at hand becomes impossible to solve. This is precisely what has happened with stuttering since the development of speech pathology over 80 years ago.

Let me give you a little background. The birth of speech pathology is attributed to Carl Seashore who back in the early 20s was head of the Department of Psychology and the dean of the Graduate College at the State University of Iowa.

Although interest in speech and hearing processes was developing in a number of universities, it was Seashore who really molded the new discipline.

The next point I find particularly interesting. Originally, speech pathology was not just focused on the production of speech. Rather, it was conceived as an interdisciplinary specialty that focused on the scientific study of human communication. And listen to what it included — psychology, speech, psychiatry, otolaryngology, pediatrics, child development. In short, it was a discipline that looked at the whole person.

Now, into the picture comes Lee Travis. In the early 1920s, Lee Travis was a brilliant undergraduate at Iowa. Seashore recognized the potential of the young student, and in part, designed the new specialty of speech pathology around Travis’ talents. In 1924, Travis became one of the first people in the world to receive a Ph.D. based on study in this new field.

Travis stayed on at Iowa and headed the program through the 1930s, a period during which many of the future leaders of the field ended up as graduate students.

In the late 30s he left Iowa to become a professor at the University of Southern California. When Travis left Iowa, Wendell Johnson, one of his prize students, took over the speech program.

Johnson was a different kind of bird. Whereas Travis was basically a research scientist, Johnson’s interest was in developing effective therapy programs. He had made a name in General Semantics, and his diagnosogenic theory soon became the prevailing view of how stuttering developed. Johnson maintained that stuttering was caused by the parents’ misinterpretations of their child’s speech. They confused the child’s normal dysfluency for stuttering. In doing so, they required from the child a level of performance that the child could not attain. The subsequent reactions of both child and parents resulted in a worsening of the child’s speech.

By the early 1940s, the way people viewed stuttering was being influenced by four widely accepted misconceptions. First, there was the belief that all the various different kinds of stuttering were basically a manifestation of the same problem. This idea goes all the way back to Lee Travis. Listen to this quote from a chapter on how to deal with stuttering that Travis wrote in 1926 for a book called The Classroom Teacher.

“Basically,” said Travis, “stuttering and stammering are the same; practically, there is a slight difference. Both are due to the same causes and consist in the malfunctioning of the same mechanism, yet there is a slight difference in this malfunctioning.

“Stuttering,” said Travis, “may be thought of as an inability to combine syllables and words into words and sentences, which results generally in the repetition of the sound or word causing the difficulty. It is in the majority of cases an incipient form of stammering.

“Stammering, on the other hand, is a complete block in the flow of speech. At times the individual seems utterly incapable of producing the desired sound. He is, for the time being, obliged to give up entirely his efforts at speech production.”

Travis goes on. “More often the same person will stutter one time and stammer another. In this discussion stuttering will be used to include both terms.”

Believing that all stuttering was essentially a variation on the same theme was misconception number one. And it caused more confusion through the years.

Misconception number two was fostered by Wendell Johnson. His diagnosogenic theory, as I mentioned previously, focused on the way the parent related to the child’s speech. That, according to Johnson, was what caused stuttering. Period. End of discussion.

Well, he didn’t have the answer. All he had was a PIECE of the answer. But as a result, people stopped looking for any other contributing factors.

The third misconception came about because many of Johnson’s students at Iowa were headed for jobs in the school system. What do teachers and parents and school administrations look for? They look for fast, efficient answers. If Johnny can’t read, let’s teach him to read. If Johnny can’t do math, let’s teach him math. And following the same logic, if Johnny can’t speak properly, then let’s teach him to speak properly.

It built on the belief that stuttering could be addressed with a simple, direct approach, similar to how you might approach an articulation problem. Once again, it discouraged people from looking at the whole person.

The fourth misconception had to do with the belief that a third party observer could determine to a certainty whether or not someone was stuttering. Most stuttering research involved third party observers. I’ve had people tell me, “I know you’re a stutterer because I heard you stumble on a few words. The truth is, someone may be fairly disfluent and yet be totally relaxed and unselfconscious about their speech and never once actually block. Another person may sound totally fluent, and yet may be doing a great deal of avoiding and substituting and be living in constant fear of blocking.

What was lost over the years was the original idea that dealing with stuttering called for an interdisciplinary approach that addressed the entire person – their emotions, perceptions, beliefs, intentions, physiological make-up as well as the physical things they did when they spoke.

What I’m saying is that almost a century ago, when people attempted to characterize stuttering and how to address it, they did the best they could at the time.

But they got it wrong.

And those misconceptions have been perpetuated to this day and accepted as truth.

As a result, the first professors of speech pathology installed the wrong paradigm of stuttering in their students. Some of those students became professors, themselves. And they, in turn, passed along the same misconceived paradigm to their students. And so it went from generation to generation.

By the way, this kind of thing has happened in other areas. I remember when it was a commonly held belief that peptic ulcers were caused by worry and an overly acidic stomach. Then in 1982, Dr. Barry Marshall right here in Perth discovered that most peptic ulcers are actually caused by H. piloroi bacteria and could effectively be treated by antibiotics.

Until then, treatment of peptic ulcers was not very effective, because doctors were looking at these ulcers through the wrong paradigm. That’s the same thing that happened with stuttering.

Why didn’t anybody question the model of stuttering? First, the problem was very complex and therefore, very elusive and hard to define. The contributing factors were all things that lurked beneath the surface.

Secondly, the opportunities for self-discovery that exist today did not exist back in the 40s and 50s. Third, we in the west were not used to thinking holistically. Interdisciplinary studies were not very prevalent when I went to college. Every discipline was fit into its own separate pigeonhole.

Finally, there was little likelihood that students would challenge accepted beliefs. For one thing, they didn’t have the background to do that, especially if they didn’t stutter themselves. Would YOU have challenged the information in YOUR textbook? So the basic misconceptions of 80 years ago were passed along as the truth from one generation of teachers to the next. This made it extremely difficult for anybody to think outside the box.

But things began to change due to several major developments. The first was the evolution of holistic thinking, thanks to ideas coming to the West from Asia and to the evolution of new computer technology.

The second was the personal growth movement, which in the early 60s was just then taking root in California.

And the third, in the late 80s, was the birth of the Internet.

I came to San Francisco from New York in 1961. It was one of the best moves I ever made. Not only was northern California a Mecca for those seeking a different way of life, it was also the center of the burgeoning technology industry in Silicon Valley. As an advertising copywriter, I was exposed to systems thinking as I turned out promotional material for technology companies on the San Francisco peninsula.

I got to read the trade publications, and although a lot of it was over my head, I could usually pick up the gist of what they were saying. I saw how systems interacted and how and why computer intelligence was possible. I could see how, when you combined the right elements together, you could come out with something entirely new…something that was greater than the sum of the parts.

The second major development, as I mentioned, was the personal growth movement that began in California just about the time I came west. Two years with a psychoanalyst didn’t do much for me, but being a participant in self-discovery groups did. I got involved with them….not because of my speech, which was bearable…but because I was living on my own 3,000 miles from home without a clear sense of who I was. I was suffering enormous separation anxieties because I was away from the people who defined me, and I was unable at that time to define myself. And so, at the age of 26, I was feeling very desperate.

I made some enlightening discoveries in those groups. I discovered that I was a very emotional person who long ago had buried his feelings. And that wasn’t all.

I had a major self-assertion problem. I was afraid to speak my truth and say what I wanted. I was an approval junkie. I wanted everybody to like me and was devastated if somebody didn’t approve of what I did. I was overly impressed by authority. If I said “red” and somebody else said “blue,” I would automatically assume that it was blue. I didn’t trust my intuition. I had little self-confidence and self-esteem. And I was a perfectionist who was constantly afraid of doing something wrong. In short, I was so busy pleasing others that somehow the real me got lost.

As a by-product of three years of intense interaction with others in a group environment, I began to see that my blocking was not primarily a speech problem. Sure, my speech was involved, but even though I had figured out what I was doing when I blocked, that knowledge was only a small piece of the puzzle. My blocking MOSTLY had to do with the difficulties I had with the EXPERIENCE of EXPRESSING myself to others. That’s what drove the speech blocks.

I began to see that my stuttering was not a single problem, but a constellation of problems in a dynamic relationship.

It’s like this Lego car. I got this car at Toys R Us in San Francisco. But if you go into Toys R Us and look for this car, you know what? You won’t find it. You will not find this car. What you will find is a box of parts. It’s up to you to put the parts together in the right way to create the car.

That’s what I discovered about the nature of speech blocks. It’s not just any one element by itself that creates the blocking behavior. It’s how these elements go together. It’s about how they relate to one another.

This is why researchers looking for the cause of stuttering haven’t been able to find the answer. There’s nothing exotic about the parts of the system. What’s exotic is in how the parts come together.

So what are the parts?

Stuttering can be more accurately understood as a system involving the entire person—an interactive system that’s comprised of at least six essential components: behaviors, emotions, perceptions, beliefs, intentions and physiological responses.

This system can be visualized as a six-sided figure—in effect, a Stuttering Hexagon—with each point of the Hexagon connected to and affecting all the other points. It is the moment-by-moment dynamic interaction of these six components that maintains the system’s homeostatic balance.

You’ll understand this a little better when I tell you about the Hawthorne Effect. Anybody know what it is?

For many years until the breakup of AT&T, Western Electric Company was the manufacturing arm for all the phone companies of the Bell System. In the 1920s, the Western Electric plant in Hawthorne, Illinois, employed a small army of over 29,000 men and women in the manufacture of telephones, central office equipment, and other forms of telephone apparatus.

In the mid-20s, the plant began a series of studies on the intangible factors in the work situation that affected the morale and efficiency of shop workers. They figured – “Hey, we make so many parts here that even if we can increase production 1 percent, that can add up to big numbers. So let’s see if we can figure out how to improve worker output.”

In particular, the company wanted to know whether changing the lighting, break schedules, and other workplace conditions would lead to higher production.

One of the earliest experiments involved a group of six women from the coil winding production line. These volunteers were pulled from the line and relocated into a smaller room where various elements such as lighting, room temperature, and frequency of work breaks could be manipulated.

The first experiment looked at whether changing the intensity of the lighting would have a positive impact on production. The experimenters started out with the same lighting intensity the workers were used to on the production line. They then increased the light a few candlepower.

Production went up.

Wow. Were they excited! They really had stumbled on something. So they increased the room light by another few candlepower.

What do you think. Did production go up?

You’re right. Production went up again.

By now they were sure they were really onto something. So they continued to increase the room lighting a little bit more until the lighting in the room was several times the normal intensity. And each time they did, the production of the six women went up.

At this point, the researchers were really pleased with themselves.. But being good scientists, they felt they should validate their hypothesis that the lighting made a difference. So they brought the lighting back to the original starting point and dropped it by a few candlepower.

What do you think happened? Production went up.

So they dropped it even more. And once again, production went up. They continued to reduce the lighting in the room until the women were working in the dimmest of light. And production continued to rise until the lighting was so dim that the women could barely see their work. At that point, their output leveled off.

What do you think was going on?

The researchers finally determined that it wasn’t the lighting or any other environmental factor that accounted for the increase in production. It was the development of a social system. Something they weren’t even paying attention to.

Before the experiment began, the women were just cogs on a production line. They lacked any sense of importance. They had few meaningful relationships with their co-workers. Their supervisor was seen as an adversary. They had little personal responsibility for turning out a quality product. Someone else set the standards, and they just performed according to instructions. There was not much pride in what they did.

In short, it was just a job.

But all this changed when the six women were pulled from the production line and given their own private workspace. From the very beginning they were special, and they loved the extra attention. Each of the women was not just an impersonal face on the production line. She was now a “somebody.”

Because the women were organized into a small group, it was easier to communicate with one another, and friendships blossomed. The women began socializing after hours. They even began to visit each other at home. They joined together in recreational activities like picnics.

The relationship with their boss also changed. Instead of being feared, he was now someone they could turn to. A group identification formed, and with it came pride in what they did.

The improvements that took place were primarily explained by the impact of the social system that formed and the ways in which it impacted the performance of each individual group member. The authors of the study concluded that:

The work activities of this group, together with their satisfactions and dissatisfactions, had to be viewed as manifestations of a complex pattern of interrelations.

In other words, it was changing the nature of the social system that mostly accounted for the change. Over time, this phenomenon came to be known as the Hawthorne Effect. The Hawthorne Effect goes a long way to explain what causes the blocking and struggling we label as “stuttering.” The Hawthorne Effect also explains why stuttering therapy does or doesn’t work. And it explains why it’s hard to maintain your gains in the outside world.

What I want suggest is that when therapy does work, it’s not just the fluency techniques employed by the therapist that account for the improvement. Often, the speech therapy only plays a minor role. It’s the speech related therapy plus the personal relationship between clinician and patient that leads to a greater level of confidence and self-acceptance on the part of the client.

The more the client feels okay about himself, the less he blocks his spontaneity, and the more he’s willing to reveal his true self. Ultimately, this can lead to a dissolution of the holding back that underlies his speech blocks.

In short, fluency is to a large degree a by-product of the Hawthorne Effect. In fact, once you adopt this explanation, you can explain just about any question that anyone has ever had about stuttering.

Let’s set up a hypothetical situation. Let’s say that, as someone with a stuttering problem, you decide to work with a speech therapist. Let’s call him Sean. Sean has set up a two-week intensive program for a half dozen clients and is holding it at a local hotel. You’ll not only attend the program, you’ll also live at the hotel during that time…away from your familiar environment in a whole new world.

In addition, let us say that Sean employs a fluency shaping approach, which involves hours and hours of practice. In the first week you will also learn a whole lot about how speech is produced so that you can visualize the process in your mind. The second week is then spent practicing the technique in real-world situations, such as on the telephone, on the street, and in shops and restaurants.

At the end of the first week, you begin to see real progress. You have now demystified your stuttering by learning what’s going on in your voice box when you block. And because of the electronic feedback, you can now distinguish the difference between tight and relaxed vocal folds, something you were not aware of before. All this is very helpful.

But is that all that is going on?

Hardly. There’s a lot more, and it relates to the Hawthorne Effect.

Sean is an open and accepting person, and as you interact with him, you feel totally self-accepted, even during difficult speaking situations. Virtually every communication between you and Sean is designed, not just to pass along information, but to bolster your self-esteem. Every piece of negative feedback is accompanied by a positive statement that reinforces the idea that you’re okay. Sean really listens to all your concerns, and he shows infinite patience in exploring the issues with you. Nothing you say is ever devalued. And that’s true in your relationship with all the others in the training as well.

If you were in that situation, how would that affect you?

Pretty obvious. You begin to trust. Your self-esteem builds. Your self-confidence grows. And you become more self-accepting.

Now, in this environment, does it feel safer to express the real you? Well, sure it does. You feel acknowledged. You feel accepted. You feel validated. You’re no longer in crisis mode. All these positive changes begin to organize themselves into a self-reinforcing system that leads to letting go, and in many cases, to fluency which is a by-product of letting go. That is the Hawthorne Effect in action.

So lo and behold, by the end of the two-week program, your speech is easier and more fluent. And because, by this time, the system is self-supporting, your fluency continues…at least for a while…as you go back to your regular world.

How many people have had the experience of coming out of speech therapy really speaking well?

How long did it last for?

Why did you slip back?

Chances are, you didn’t slip back because you stopped practicing the right techniques. A lot of people continue to practice proper technique and they still slip back.

Why is that?

The answer is, it wasn’t just proper technique that made you more fluent to begin with. Sure, that was important. But it was also your relationship with those around you. They were there to support you. You felt good. You felt okay about yourself. But what happened when you left the training? Was everyone in the world committed to supporting you in the same way?

Uh-uh. In the real world, people were caught up in their own issues. They weren’t thinking about you. In fact, they may have actually put their needs before yours. Imagine that! How many here have had to fight for a parking place or deal with a rude bus driver or sales clerk?

How’d that make you feel? Wasn’t it more risky to let go and assert yourself in those situations?

So what happens? If you’re not also working on the other parts of the stuttering hexagon…such as the way you think and feel…you end up reacting to these cues from other people and start losing your trust and self-confidence. Then one day you find yourself blocked. This triggers a downward spiral, and eventually you’re back where you started.

All this is due to the Hawthorne Effect that’s operating in the background.

Over the years I’ve met many people who ended up relapsing after they had spent, in some cases, thousands and thousands of dollars in speech therapy programs. Some of the stories I heard really upset me.

I’m thinking of one very popular program in the U.S. that uses a fluency shaping approach. For years, people who went through this program were told in no uncertain terms that stuttering did not involve emotions and therefore, emotions would not be addressed. They were only going to work on mastering speech technique.

That’s crazy! And yet there are many people – maybe most people — who still believe this.

It’s not that the therapists in these programs aren’t sharp. They are. It’s just that the model of stuttering that they grew up with…the model they were given in school and on which they base their therapy…is flawed. It’s the wrong paradigm.

The concept of stuttering as, not a thing but a system, explains why stuttering is so hard to change. It’s not just your speech that has to change. IT’S YOUR ENTIRE SELF. This includes how you think. What you feel. What you believe. How you perceive. What your intentions are. What your self-image is. How you speak. All this is tightly organized into an interlocking, interactive system. It’s a living, self-perpetuating system that does everything it can to maintain itself.

Try and change just one part of it and you push the system out of balance. To reestablish that balance, the rest of your stuttering hexagon will try and bring back your speech to the point it was at before you began therapy.

THE DIFFERENT KINDS OF STUTTERING

One aspect of the stuttering system that has through the years caused major problems has been the use of the word “stuttering.” The ineffectiveness of this word to describe what’s really going on has caused all kinds of problems and has led to immense confusion and muddy thinking.

Let me give you an example of how the sloppy use of language leads to problems. One of the most enduring lines of all time was spoken by Bill Clinton on TV when he said, “I did not have sex with that woman.” Clinton took a very liberal interpretation of the word “sex.” And it led to all kinds of interesting problems.

How many of you have seen Oprah Winfrey? Oprah is the most successful and admired TV personality in the world and has enormous influence on millions of people in America.

On one of her programs, the subject was young, teenage girls who were having sex. There was this one 15-year-old who was going to parties and performing oral sex on some of her male classmates and this girl didn’t thing there was anything wrong in it….something that was shocking to millions of viewers. When she was asked by Oprah whether she knew that young girls shouldn’t be doing this, you know what her response was?

“That’s not sex.”

“What do you mean that’s not sex!” says Oprah.

“Well,” says the girl, “I know it’s not sex because the President of the United States says it wasn’t.”

That’s what happens when you don’t use language precisely. It leads to confusion. And it has consequences.

The same thing happens with stuttering. What do you mean by “stuttering?”

Are you talking about pathological disfluency? Developmental disfluency? Bobulating? Blocking? Stalling? Even though they may look alike at times, they’re all different. Each is driven by a different set of dynamics.

For example, bobulating is kind of a relaxed, stumbly disfluency that you hear when people are upset, embarrassed, confused or discombobulated. The person is able to talk, but their emotions are causing them to trip all over themselves.

On the other hand, when a person blocks, they are, for the moment, unable to talk. They’re feeling helpless. That helplessness can lead to panic and embarrassment. They become self-conscious. It’s a totally different kind of experience even though it may look the same.

When you call both of these stuttering…instead of bobulating and blocking…it forces you to make incorrect assumptions just like the girl did on the Oprah show.

An ineffective vocabulary is just one reason why this problem has not been clearly understood and in most cases, incorrectly characterized and addressed.

WE NEED TO APPROACH THE PROBLEM DIFFERENTLY

What does all this mean? It means we have to start approaching the problem of stuttering in a more, all-inclusive way. If I hadn’t done that, I’d still be blocking.

Practitioners in the field need to broaden their perspective. That’s tough, because there has been in the past…and I think still exists in most places…a prejudice among professionals against those who take a holistic approach. I’ve had many conversations with speech pathologists who have taken this approach, and I’ve heard many of their sad tales.

I have a speech therapist friend, Claudia Dunaway at San Diego State University who I met about seven years ago. She had read a paper that I had delivered in a workshop at an annual meeting of the American Speech-Language and Hearing Association. Turns out, I was the first person from the stuttering community to confirm her own observations that this problem involved a lot more than just speech. She knew it did, but nobody had ever validated it for her. So when she read my article about the Stuttering Hexagon, she was so excited she flew up to San Francisco and bought me dinner. And we talked into the wee hours.

What’s interesting about Claudia is that when she was younger, she was involved in the free speech movement. Meaning what? Meaning that she spent several years exploring her feelings and her beliefs. She examined different lifestyles and her own life issues. She became very open minded and sensitive to who people were as people. She learned to look below the surface. Later on, she applied this knowledge and sensitivity and perspective to her clients very successfully when she became a speech therapist.

But talk to Claudia and her associates at San Diego State and you hear about the closed minds they encounter at professional conferences. So many of the professionals just don’t want to deal with this holistic view of stuttering.

If I have one bone to pick with the professional community, it’s that more of you don’t take advantage of the most important resource you have…the actual people who stutter…and especially, the most overlooked resource of all — those who have recovered.

I mean, if you wanted to get to the top of Everest, where would you go for guidance? Would you only talk to people who have read books about climbing Everest or those who tried to climb it but haven’t yet succeeded?

Or would you also chat with the 500 or so who have actually achieved the summit and ask them, “Hey guys, how did you do it? Tell me in detail what the problems were? What worked? What didn’t? What did you need to know? What was helpful? WHO was helpful? What did you learn? There are a hundred questions you could ask.

But do researchers seek out recovered stutterers and ask those questions?

As a member of the National Stuttering Association, I’ve been in contact with the professional community for over 27 years. How many researchers would you guess went out of their way to ask me how I recovered?

The answer is…only two! Two people in 27 years.

You saw at the beginning of this talk, how, in trying to solve the puzzle using the wrong paradigm, you could have worked on it for a week with no success.

From what I have seen, and from my own recovery, I am convinced that the mysteries of chronic stuttering have eluded us for the same reason. All this time, the pieces to the puzzle have been sitting there right under our very noses. The answers are found by using a different model of stuttering that takes into account the many aspects of the individual – his emotions, perceptions, beliefs, intentions, physiological makeup, speech behaviors – and how all of these factors are woven together to create what we call chronic stuttering.

If you professionals see us as partners, and not just patients, and if we in the stuttering community continue to play an active role by offering our own personal observations… and if we continue to share our thoughts and ideas and findings all over the Internet…we will begin to see answers to a problem that has eluded us for over 5,000 years.

So what do you say? Are you ready to challenge your old beliefs? Are you ready to open your mind to new possibilities? Are you ready to make a paradigm shift?

It’s been a real pleasure speaking with you today.

Answer to the puzzle: the numbers are in alphabetical order

My Five Stages of Recovery – How my stuttering disappeared

by John C.Harrison

Pour la traduction française, cliquez ici

People often want to know when I first became fluent, and I sometimes feel as if they’re looking for the particular moment when I could speak without blocking. It’s not like that at all. Recovery from chronic stuttering does not happen overnight, except in very rare instances.

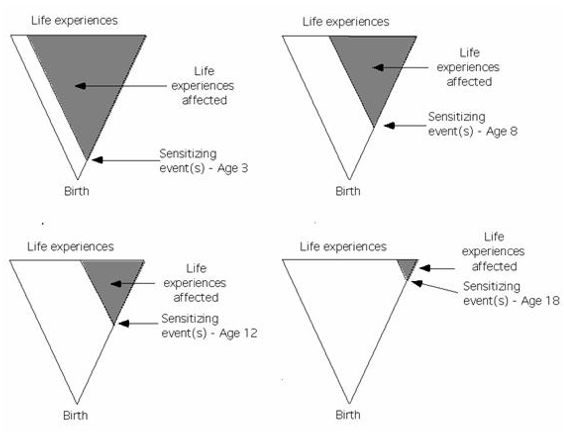

Most people change gradually, in stages, and although you can create mechanical fluency overnight with various speech techniques, true fluency occurs when the constant fear of blocking has disappeared. Your total system has changed sufficiently so that you do not automatically default to a speech block when you are under stress.

It is not necessary to achieve this level of recovery to feel that you’ve successfully licked stuttering. I know many people who are elegant, charismatic speakers, even though they still manifest an occasional block. And I know others who still have significant blocks and yet are successful people and compelling presenters. Eloquence does not revolve around fluency. It has to do with the ability to connect with people and to say what is in your heart. It has to do with being genuine. It has to do with never compromising your convictions but speaking your mind, regardless of the circumstance. This is when chronic stuttering has truly been defeated.

FIVE STAGES

The history of my stuttering can be characterized by five distinct stages: denial, acceptance, understanding, transcending, and reprogramming.

STAGE ONE: Denial.

Almost everyone I’ve met who’s had a chronic stuttering problem spent his (or her) early years in denial, and I was no exception. Why my speech would suddenly freeze up was a total mystery to me. I just knew that it happened, and I was terrified by the social consequences. I dreaded doing anything that could be made fun of, so when I blocked, I never displayed any bizarre struggle behaviors, or what the therapists call “secondaries.” I simply out waited the block until it released, and I could say the word. But those breaks in my speech were harrowing. I was very self-conscious and overly sensitive about deviating from the norm. I was your classic “closet stutterer” and distanced myself from anything that appeared even slightly out of the ordinary.

I remember one day when my father referenced the fact that I stuttered, and I immediately shot back, “I don’t stutter, I hesitate.” Though I was constantly afraid of speaking situations, such as talking in class or speaking to authority figures, I would never acknowledge that there was any problem. This mindset continued until the summer of my senior year in high school.

That summer my parents sent me to a daytime program at the National Hospital for Speech and Hearing Disorders in New York City. Not much changed in my speech as the result of my two months participation in the group since I don’t think we ever did speech therapy or modification per se. But there was one significant change in my attitude. By the end of the summer, I was willing to acknowledge that I had a stuttering problem. I could say the word “stuttering” without feeling like a pariah; however, I still had not reached a point of acceptance where I could share my problem with the non-stuttering world.

STAGE TWO: Acceptance.

Being in denial keeps you stuck, and although it may be painful to accept your present circumstances, it is essential that you do so if you want to move forward.

To create an analogy, imagine you suddenly find yourself standing in a four-foot hole. “Omygod,” you say, “I’ve really gotten myself in a hole,” as you push and struggle to climb out. But suppose you believe that smart, intelligent people should never be seen standing in a four-foot hole. Since you consider yourself smart and intelligent, and since you want people to think well of you, you immediately fall into denial about your current situation.

“Me? Standing in a hole? That’s crazy! Why would I be doing that?” you ask, but then, when you go to walk away, you find yourself strangely hampered.

Of course, the situation is absurd. Yet people cast themselves in this position all the time. Consider the individual who gets himself into a hole financially, but is unwilling to accept his current lot. “I have plenty of money,” he says. “Of course I can buy that car. Of course, I can take that vacation. Of course I can buy those new clothes.” So he spends and spends until one day everything crashes down around him.

Why would someone be in denial about his lack of funds? Because it’s scary to be in that position. If he is unwilling to feel the fear, he’ll try and change his reality into something that is more comfortable. Similarly, when people are unwilling to accept their stuttering, it’s not the actual stuttering they fear, but the feelings that are brought up when they stutter. It’s scary to feel helpless. It’s scary to feel like you’re different from other people. It’s scary stand there and not be able to talk.

But emotions are simply emotions, and choosing to experience them does not mean that you’re stuck with them forever. Quite the contrary, when you accept and experience what you’re feeling, the emotions release, and the way is open for another, more positive set of emotions to take their place.

In the fall of my eighteenth year, I left home for university.

As incoming freshmen, we were subject to various tests to evaluate our proficiencies in foreign language, English composition and mathematics. We were also called to the speech lab to see if there was any aspect of our speech that needed to be remedied. When I heard this, I was immediately on guard. My knee-jerk reaction was to hide my stuttering.

I kept my date at the speech lab and read through the required paragraph without a hitch. Had the evaluator been able to measure my anxiety level, it would have been a different matter, but I was able to pass for “normal” and left the lab greatly relieved. However, it was a hollow victory. Though I was not identified by the university as someone with a problem, in reality I very much had a problem, even though I was the only one who knew about it.

The maddening thing about my speech blocks was that they didn’t show up in everyday conversation. They only appeared when I had to speak in front of the class or in time-bound situations such as having to stop someone on the street to ask a question. This intermittent problem left me with a confused self-image. Was I a normal speaker, or was I a stutterer? I never seemed to be one or the other, and this left me in a state of limbo. I lived in constant fear of suddenly blocking with a person with whom I had been fluent up to then. I was afraid of how they would look at me. I did not want to answer their questions. And most of all, I did not want to seem strange or different.

What brought matters to a head was a philosophy class in my sophomore year. The professor, a short, intense Russian-born man, was popular among the students, and the class was large, numbering over 100. In each class the professor asked several of the students to stand and read their paper. I lived in terror of being called on, and finally went to the professor and asked if I could simply hand in the paper and not be called upon to read. He was quite amenable, but I was mortified at having to ask him to make this concession.

That was when I decided it was time to do something about my problem. The school had no speech therapist who was knowledgeable about stuttering, but I did find a professor in the speech department who said he could help me. As I recall, I didn’t see him for very long, nor do I remember much of what we did. But what he did offer me – which made a big difference in my life – was a clear and detailed explanation of how speech was produced. For the very first time, my mysterious speech blocks were correlated to specific physical behaviors. They weren’t something that struck me out of the blue. They were something I was doing, and I could actually picture how the vocal folds could close and prevent air from passing. It was the first step in de-mythifying my stuttering.

Later that year, I also took another big step in coming out of the closet. I took a public speaking class, and in one of the speeches, I gave a talk on stuttering. The cat was finally out of the bag. I still have the outline for that talk in a box of school papers. It’s one of my university mementos I’ll never throw out.

STAGE THREE: Understanding.

The seven years from the time I graduated college until I was 30 years old were marked by a dramatic increase in my level of self-knowledge. After six months of active service with the army and a two year stint working in New York City in various entry-level jobs, I boarded a plane one day and relocated to San Francisco.

By this time I was very much caught up in trying to figure out who I was and what my stuttering blocks were all about. Before I left New York, I had attended a 14-week Dale Carnegie course and had my first positive experience with public speaking. In every evening class each of us had an opportunity to make two short talks, usually no longer than 60 to 90 seconds each, after which we received vigorous applause and several positive comments from the instructor. I found out that, although it ramped up my anxiety level, I rather enjoyed being in front of people, and in the totally accepting environment of the class, I discovered I was a bit of a ham.

When I came to San Francisco, I joined Toastmasters, and eventually became president of the Chinatown Toastmaster Club. During my three years in Toastmasters (I rejoined 35 years later and am still a member), I became more and more comfortable in front of an audience.

Aside from helping me become more comfortable in front of people, these speaking programs gave me an opportunity to experiment with my speech in safe, yet “risky” situations. If you want to explore your stuttering with the intent of understanding what it’s about, you must put yourself in a variety of speaking situations. And this is precisely what I did.

I began to notice some interesting things.

I discovered that if I released a little air before I spoke, it often made speaking easier. Some years later, I discovered that Dr. Martin Schwartz had developed an entire therapy around this airflow technique.

In addition, whenever I blocked, I would also routinely repeat the block to see if I could discover what I had done to cause it. Then I would repeat the word without blocking. I later learned that this procedure is called cancellation and was a technique regularly used by Dr. Charles Van Riper.

What I have come to realize is that most of the techniques used by speech clinicians can be figured out by an enterprising stutterer who’s willing to experiment.

I was also helped by my involvement with a unique organization that helped to foster my development as a person. Synanon was started in the late 1950s by Charles Dederich, a recovering alcoholic, as a 24-hour residential facility where recovering drug addicts, felons, and other acting out character disorders could be brought back into society. It was an organization that ran strictly by the seat of its pants, without any government funding. The underpinnings of Synanon were honesty and self-reliance.

Their major vehicle for self-discovery was a group interaction called the Synanon Game. This was a group dynamic without formal leadership where you could develop proficiency in confronting yourself and others. The only rule was that there would be no acting out of feelings, except through verbal expression. People were free to run through their whole range of emotions. The game would be focused on an individual’s unacceptable behavior, and that individual would feel compelled to defend himself.

The subtle ways of getting people to see the truth was often awe-inspiring. The leadership in the group shifted from one person to the other as an individual took on the job of building an indictment against an individual for some kind of unacceptable behavior. Experienced people played the most dominant roles, and the way you gained experience and proficiency in the game was to look, listen, defend, and attempt to lead the charge in building an indictment on somebody else. People were verbally cornered into exposing their lies and weaknesses as they tried to make themselves look good.

Ironically, individuals looked the best when they were completely honest, open, candid and forthcoming. They looked their worst when they tried to defend themselves and hide. Moment by moment, it was a big verbal free for all, sometime soft, often loud, frequently funny. Any emotion was fair game, provided it stayed as an emotion and was not acted out.

The game was also very, very manipulative. Those who were in touch with their emotions and could express them easily and openly played the most powerful roles. This also helped to build skills in dealing with society at large.

As newcomers came back week after week, they, too, began to build their own skills as they dug deeper into their own emotions and peeled back the layers of their own personality. The only hard and fast rule was – no physical acting out.

Today, the concept of personal growth and development in a group setting is commonplace with many kinds of creative programs available to the public in many countries. These by and large follow a much gentler approach. (Keep in mind that the Synanon game was designed for hardcore drug addicts and other character disorders). But even today’s personal growth programs, like the Landmark Forum, which is available worldwide, have advanced programs where the environment becomes more challenging.

I should emphasize, however, that formal programs of any sort – either in speech or in personal growth – are not essential if you’re a good observer and have the willingness to put yourself at risk. But it does help to have people in your life who are of like mind and with whom you can share your challenges and successes.

When I began my involvement with the Synanon Games, I could not say more than a few sentences before my anxiety level went through the roof, causing me to become uptight and stop talking. I was totally intimidated by stronger personalities, and always felt I had nothing of value to say. It was a year into my involvement with the Synanon Games that I had my first breakthrough. One night, all the strongest and most experienced people in the Game were absent, and I found myself among the most season people present. Suddenly, my mouth became unshackled. Without authority figures in the room, I began assuming roles that just a week before I would have totally avoided. And you couldn’t stop me from having my say.

STAGE FOUR: transcending.

I stayed involved with Synanon for about three years, during which I participated in a variety of activities. They ranged from two-day stay-awake marathons that helped us probe deeper into our psyches to hawking tickets to a boxing match with nationally ranked fighters at a local sports palace. This was a big fundraiser for Synanon and a huge stretch for me who had always hated to ask people to do anything for fear of rejection. These activities that pushed me out into the larger community played an important a role in my recovery.

Throughout all this, I tried to remain a good observer of myself, and very slowly, a new picture of John Harrison began to form. I wasn’t as nice or as good as I thought I was. I saw sides of myself I wasn’t proud of. I saw how I routinely capitulated to those who I felt were stronger or more knowledgeable. And I got in touch with how much anger I’d been holding in since I was a little boy.

In this open environment, I began to understand that my speech blocks were only marginally about speech. I saw that at the heart of it, I was blocking out my own experience of myself. I was trying to present myself from knowing and experiencing ME. The awful me. The arrogant me. The scared me. The pushy me. The weak me. The strong me. All those me’s had been suppressed years ago as I tried to adapt to what I thought the adult world wanted of me.

Once the genie was out of the bottle, so was my ability to express myself. When that combined with all the work I’d done in building awareness of my physical blocking process, I began speaking more easily and with only infrequent difficulty.

STAGE FIVE: reprogramming.

As I carried what I learned into the larger world, my default behavior – the automatic blocking behavior that I had built up during my first two decades – slowly weakened and gradually disappeared. Simply understanding what my blocking was about was not an automatic cure. This was, after all, a survival strategy that had been ingrained into every muscle and fiber of my being. Even though they happened only infrequently, I still hated those blocks. I was still uneasy around authority figures. But now I knew that those fears would only go away if I taught the primitive part of my brain – the part that initiated the fight or flight response – that these were not life-or-death situations.

Chronic blocking and stuttering is like a large black spider. There’s nothing inherently frightening about spiders. After all, spiders don’t scare entomologists. There are actually people who keep tarantulas as pets and pick them up and allow them to walk up and down their arm.

So it’s not the spider we fear, but the feelings they bring up. We see the spider as a threat, and our sympathetic nervous system triggers an instant flight-or-fight reaction to protect us from a perceived danger. But if the spider is no longer perceived as a danger, the feelings are not triggered.

Changing default behavior is like anything else. It comes through practice and persistence. It’s like the martial artist student who one day is surprised that he automatically did the right thing when attacked by an opponent. The recovering stutterer discovers one day that he just spoke without thinking in a situation where normally he would have never risked speaking.

And if he happens to block, he says, “Oh look at that. I just blocked. I wonder what’s going on?” Then he can review what he experienced and what he did and heighten his awareness of his automatic fear response. In so doing, he can stop himself from slipping into a full-blown panic response.

If he (or she) has studied an approach for managing the block such as McGuire technique, air flow or fluency shaping, he can call that up to handle the mini-crisis, and then slip back into automatic speech.

By and large, for those who have beaten chronic stuttering and blocking, communicating has become fun, and they welcome any opportunity to talk. Remember that the bottom line is not perfect fluency. Some people will naturally be more fluent than others. The bottom line is whether you can say what you want, the way you want, when you want, and to whom you want. And whether you can truly show up as yourself.

POSTSCRIPT

As I was finishing this piece, I found myself wondering whether some PWS will take all this as a precise blueprint for their recovery. So I would like to add this postscript.

These five stages of recovery described here are five general stages. Your details will be different because after all, you and I are different people. We see things in unique ways. We have different backgrounds and experiences. Each of us has his own personal story.

What’s important is to understand the essence of each stage so that you can apply it to your own recovery. Through the years I’ve observed recovery as an evolutionary process. And if a person tries to jump over something that requires attention, his or her psyche will make it difficult to accommodate the change.

The only time that quick fixes seem to work is when the individual has already laid the groundwork for recovery. Everything is in place. They are a recovered person just waiting to happen.

John can be reached at . His book REDEFINING STUTTERING is available from Amazon. It is also a free download at http://holdingback-forpeoplewhostutter.weebly.com

More Articles by John Harrison

See several articles by John Harrison on the Minnesota State University Mankato Web Site

Understanding the Speech Block

John C. Harrison

At the heart of chronic stuttering — specifically, the kind of dysfluency that ties you up so you momentarily cannot utter a word — is something called a “speech block.” We have traditionally seen speech blocks as having a life of their own, mysterious and unexplainable. Speech blocks seem to “strike” us at odd moments, usually without our knowing why.

You’re standing in line at Macdonalds, about to say “hamburger,” when suddently, a speech block zooms out of the ether and (WHUMP!) hits you in the vocal cords and renders you speechless.

The blocks seem as if they are not connected to us, giving rise to such phrases as “I was hit by a speech block.”

In response, we search for explanations. You hear statements such as, “Speech blocks are genetic.” — a prime example of using one unknown to explain another.

But when you understand what a block is about, it begins to make sense. There is no need to resort to such esoterica as genetics. Sometimes, simple explanations are the most compelling.

Opposing forces

I’d like to invite you to undertake a little exercise. Hook your hands together with your elbows pointed outward in opposite directions. Now try and pull your hands apart while making sure that your hands stay locked.

This is an example of a block. You have two forces of equal strength pulling in opposite directions — the force you’re exerting to pull your hands apart opposes the force you’re exerting to keep your hands locked together. As long as the two forces are equally balanced, you remain blocked.

If you want to get past the block, what are your options? Well, you can.

- decide to stop trying to pull your hands apart;

- decide to stop clamping your hands together;

- decide that this silly demonstration is not worth wasting another moment of your time and go do something else.

Any of these alternatives will instantly resolve the block.

Let’s look at what these three options have in common. All of them involve your intentions — in this case, your conflicting intentions. The block is caused by attempting to do two things simultaneously that pull you in diametrically opposite directions — pull your hands apart and hold them together.

How does this relate to speech?

A speech block is created when you intend to do two things that are directly opposed to one another. As long as you keep trying to do them both, you will experience yourself as blocked.

Shooting the horse

To better understand the nature of a block, let us examine it within a totally different context. Let us say that one beautiful summer afternoon you’re riding your favorite horse in the back country. Your mount is a splendid Arabian that you’ve raised from a colt. Riding this gallant steed has become your most beloved pastime, and over 15 years the two of you have become fast friends. When you’re not riding, you’re in the stable, grooming the horse and caring for it.

Today, as you canter through the tall grass, you’re lost in a magical, timeless world. Then suddenly, disaster! Your world collapses! The horse steps into a hidden hole, crashes to the ground and hurls you over its head. You roll. You pick yourself up, knees and elbows raw. But you’re oblivious to the pain, because the unthinkable has happened. Your best friend, the Arabian that you’ve loved for 15 years, is lying on the ground with its leg broken. It is in pain. It is suffering. It cannot be saved. You know that the only humane thing is to put it out of its misery. Right here. Right now.

Because this is snake country, you have gotten in the habit of wearing a side arm. You have one with you now, a .38 colt. You draw the pistol, and walk slowly up to the horse. You can see its pain. This has to be done. You stretch your arm in front of you, hand gripping the .38. You aim the pistol at the horse’s forehead, and slowly squeeze the trigger.

But your finger freezes. The horse is looking straight into your eyes. You look back. This is your best friend. How can you possibly pull the trigger? You think of all the years you’ve spent together, all the happy hours in the back country. How can you just stand there and kill your best friend?

You try again, but again, you cannot get yourself to pull the trigger. Your index finger is rigid and won’t move. You’re aware of what’s holding you back. You are not willing to experience the grief you know will arise the second after you pull the trigger, the pistol lurches in your hand, and the horse’s eyes glaze over. You just cannot pull the trigger!

At this moment you are experiencing a block. Two forces of equal strength are pulling you in opposite directions. Pull the trigger and lose your best friend. Don’t pull the trigger, and cause your best friend to suffer needlessly. You find yourself frozen.

How can you get past the block?

You can choose not pull the trigger and allow the horse to suffer, or perhaps have someone come and do the job for you. Another option is to pull the trigger and accept the pain you’re sure to feel. Whichever route you take, to get past the block, something has to give.

Losing self-awareness

Were you in this position, there would be no mystery about what was going on. You’d know why you couldn’t pull the trigger. You loved the horse, and the pain of shooting it was something you could not bear.

Now let’s modify this story. Let us say that you were out of touch with the fact that you cared for the horse, because you traditionally hid your feelings from yourself. You were just not the type to admit that you cared.

Okay, same scenario. The horse falls and breaks its leg. You draw your pistol and point it at the horse. You start to squeeze the trigger, and again, your finger freezes. But now, the frozen finger is a mystery, because you are out of touch with your feelings. You do not allow yourself to know that you care for the horse, although you care terribly. You have pushed this caring out of your awareness. Nevertheless, the fear of having to confront those feelings is holding you captive. Some thing is stopping you from pulling that trigger. It seems beyond your control because you’re out of touch with your fears about shooting the horse. It’s a matter of will. What is stopping you is your own reluctance to act.

The speech block

This is analogous to what happens with a speech block. You have a divided intention — speak/don’t speak. But because you have learned to prevent yourself from experiencing painful emotions, you close up and hold back. You push the fear (embarrassment, discomfort, etc.) out of your conscious awareness.

Thus, the block seems outside of your control, because you’re only aware of half the conflict. You know you want to speak, but you are not aware of the simultaneous reluctance to speak because of the underlying fear and pain. You hold yourself back without being aware you’re doing so. That is why speech blocks seem to happen to you.

The antidote is to begin paying attention to what you’re feeling…or at least start noticing and questioning what’s going on when you block. The most compelling question I used to ask myself when I was afraid of blocking was, “Suppose I do speak right now in this situation. What might I experience? Usually, the first thing I thought of was, “I might stutter.” Perhaps. “But what else, might I experience?” Here’s where so many people go blank. They simply don’t know what else might be lurking down there.

Is it a fear of asserting yourself…of looking aggressive or coming on too strong…of being the real you? Usually, the problem lies in this area. There is something about yourself that you feel is unacceptable, so you hold back until it feels safe to talk. “Safe” means that you can now talk because the intensity of the feelings has dropped and you can now remain within your comfort zone.

A second scenario

Just to confuse things, there is another, completely different scenario that can also lead to a speech block. It, too, involves a divided intention, but it is driven by different forces. It has to do with one of the body’s natural responses — the valsalva reflex.

William Parry in his excellent book, Understanding and Controlling Stuttering (available from the National Stuttering Association or from Amazon) postulates that a speech block can result from the misapplication of a valsalva maneuver.

What is a valsalva maneuver? A valsalva maneuver is what your body does whenever you try to lift a heavy suitcase, open a stuck window, give birth, take a poop, or do anything that involves a concentrated physical effort. Your chest and shoulders become rigid. The muscles in your abdomen tighten. And your throat — in particular, your larynx — becomes completely locked. The locking of the larynx is the body’s way of closing the upper end of the windpipe in order to keep air in the lungs. It is called an effort closure.

Why does your body do this?

Blocking the upper airway at the same time as you tighten your chest and abdominal muscles puts pressure on your lungs and creates internal pressure. This, in turn, creates strength and rigidity. It allows you to push harder. It gives you strength. It’s why four inflated tires can hold the weight of a heavy automobile.

Initiating a valsalva maneuver makes sense if you’re lifting your new 32-inch TV onto its stand. You need the added strength. But it is a non-productive strategy if you’re asking someone where the post office is, and you expect to have difficult saying “post,” so you start preparing yourself to push the word out. The very muscles that are tight and rigid and clamped together to give you strength are muscles that should be soft and pliant and relaxed in order to create the resonant tones associated with speech. No wonder you can’t speak.

Then why do we tighten everything?

Professor Woody Starkweather in an e-mail on the Stutt-L listserv on March 29, 1995, offered an excellent description of how some children end up misapplying the valsalva maneuver as they first struggle to learn to speak. Here’s what Woody said:

Personally, I think that most “garden variety” people who stutter (PWS) when they are very young find themselves repeating whole words. At this point, they aren’t usually struggling (there are exceptions), but they are still being impeded in their ability to say what they want to by these sometimes long, whole word repetitions. Their first reaction to this is usually frustration. They want to talk and they can’t go forward as quickly as they want to. Typically, this happens between two and four years of age.

At this age, the most common strategy for a child to use who is hindered by something in a task he or she wants to perform is to push hard. If something is in your way, you push it out of the way. The idea that some things work better if you don’t try harder is an alien concept to the preschool child, by and large. So they start to push the words out, and it works a little and some of the time because eventually the word does come out, in spite of the pushing, and it feels as though the child has pushed it out.

So he or she learns to push (with subglottal air pressure) when they feel stuck, and a nonproductive, maladaptive strategy for coping with stuttering has been born. The effect on the stuttering behavior is that the repetitions get shorter, i.e., part-word instead of whole word, blockages may increase because at a certain threshold of pushing the vocal folds clamp tighter together (the valsalva reflex), and the tempo of the repetitions increases because pushing harder usually also involves trying to talk faster through the stuttering behavior, that is, trying to stutter faster to get it over with.

There are a variety of strategies — some kids focus on speeding up during stuttering, others just push hard, others learn very early to avoid by turning away, stopping talking, saying “never mind,” etc. And I believe quite strongly that the only way to recover from this problem is first to become very aware of what you are doing during the stuttering. For an adult, this will usually involve learning about even more strategies that have been layered ontop of those early ones, but eventually the PWS comes to know and understand those very early pushing, speeding up, and avoidance behaviors.

Building awareness

So there you have it. Not just one but two credible explanations for what causes a speech block, and not once did we have to mention genetics or faulty brain functions.

Losing awareness of your intentions is not specific to stuttering. People develop blocks around all sorts of things. I once knew a guy who was not able to urinate in a men’s room whenever someone else was in the room with him. Same problem. For whatever reason (usually such fears are deep-seated) he held himself back by tightening his sphincter, but he didn’t know he was doing this. He just knew he couldn’t urinate. When the person left the room, then his sphincter relaxed, and he could complete his business.

As with most problems like this, the recovery process begins by developing your awareness of what’s going on and bringing these unconscious behaviors back into consciousness. This calls for observing each blocking situation carefully, perhaps keeping a diary so you can keep track of what threads are showing up consistently from one blocking experience to another.

Do you block around authority figures. Do you block when you’re afraid you’ll be wrong. Or when you’re afraid of looking foolish? Or aggressive? Or embarrassed? Do anxious feelings come up when you have to assert yourself?

Do you notice that each time you block, you also seem to be holding your breath? What else do you notice you’re doing? What else can you begin to bring back to conscious awareness.

Either of the scenarios I described above can cause a speech block. And sometimes, both are operating at the same time. So you really need to pay attention. Nobody said that recovering from blocking is easy. It’s not. But making the effort — and keeping at it — will eventually pay off by helping you take conscious control of an unconscious reflex.

How I Recovered from Stuttering

A keynote speech by John C. Harrison to the Annual Meeting of the

British Stammering Association London, September 8, 2002

John C. Harrison

It is always a pleasure to come to my favorite city. Especially when I get to talk about my favorite topic. Stuttering had a big impact on my life, and I wrestled with it more or less for 30 years.

My stuttering was always very situational. Around my friends, I could generally talk okay. But if I had to speak in class, or talk to authority figures, or get on a bus and ask for a “transfer, or stop a stranger on the street, I’d block. And as far as standing up and speaking in front of a group…forget it.

And yet I recovered. When I say I recovered, I don’t mean that I’m a controlled stutterer. I mean that the impulse to block is no longer present. It’s gone.

Now, according to most people, that’s not supposed to happen. I’ve heard hundreds and hundreds of people say, “There’s no cure for stuttering. Once a stutterer, always a stutterer. Nobody knows what causes stuttering.” Many of those people have been in the professional community. Mostly, they talk about controlling one’s stuttering. But they don’t talk about disappearing it.

That at least some people can make their stuttering disappear — and I’ve met a number who have — is an important statement on the nature of stuttering. That’s what I’m here to talk to you about…the nature of stuttering.

The reason why we haven’t been more successful in addressing it over the last 80 years is that for all this time…in my opinion and in the opinion of a growing number of others…stuttering has been incorrectly characterized. We’ve been using the wrong paradigm. We’ve been solving the wrong problem.

If you’re trying to solve a problem, the way you define and frame the problem has everything to do with whether you’ll be able to come up with an answer.

Employing the right paradigm is important because a paradigm filters incoming information. Anything that doesn’t fall within the defined characteristics of the paradigm is deemed to be unimportant and irrelevant, although much of what remains unnoticed may be necessary to solve the problem.

Another reason why we’ve been stuck in our thinking about stuttering is that, by and large, most of us focus our attention in looking for answers in all the familiar places.

It’s like the man who’s walking home one night, and comes to a fellow on his knees under a street light, obviously looking for something.

“Hey, buddy, need some help?”

“Sure do,” says the man. “I lost my car keys.”

“Well, let me give you a hand,” says the passer-by. And for the next five minutes they both crawl around under the street light, looking for the keys.

Finally, the passer-by says, “Are you sure you lost the keys here?”

“Oh no,” says the man. “I lost them over there,” and points to a section of grass outside of the light.

“Well, for Pete’s sake,” says the passer-by in frustration. “Why are you looking here?”

“Light’s better,” says the man.

The reason why I’m standing here talking to you today, having disappeared my stuttering, is in part because I never looked for answers in the “well-lit” familiar places. Why? Well, for one thing, I had a simple block and never developed a lot of secondary behaviors. Therefore, I never worked with a speech therapist. Therefore, I never got into the traditional thinking about stuttering as something you had to control. Therefore, my search for answers was not colored by other people’s ideas. I was not told what was important and what was not. I never developed the familiar filters through which most people viewed stuttering. And that’s why I was able to see more clearly what was going on with my speech.

What I discovered over time was that my stuttering was not about my speech per se. It was about my comfort in communicating with others. It was a problem that involved all of me — how I thought, how I felt, how I spoke, how I was programmed to respond. And yes, there were also some things I did with the muscles that created speech that I needed to correct.

Before we go on, there’s something we need to do. We need to define what we mean by “stuttering.”

The easy disfluencies that many people experience in emotional situations are essentially different from the struggle behavior characteristic of a full-fledged stuttering block. One is a reflex triggered by emotions and probably influenced by genetic factors related to how one relates to stress, etc. The other is a learned strategy, a set of behaviors designed to break through or wait out a speech block. They are, in short, not simply points on a continuum but entirely different phenomena. By using a common name, we imply relationships and similarities that may not in fact exist, and it only creates endless confusion to call them by the same name—”stuttering”—even if we distinguish one as “primary” and the other as “secondary”.

For this reason, I propose that we give up the word “stuttering” (except in the broadest of discussions) and differentiate each of five different behaviors by assigning to it its own separate and unique terminology.

- The dysfluencies related to primary pathology such as cerebral insult or intellectual deficit we’ll call pathological dysfluency.

- The disfluencies that surface as the young child struggles to master the intricacies of speech we’ll call developmental disfluency. This has a developmental model all its own which is separate and distinct from the developmental model of adult blocking behavior. Developmental disfluency often disappears on its own as the child matures. It is also highly receptive to therapeutic intervention, so much so that when treated early enough, most children attain normal speech without any need to exercise controls.

- The easy and unselfconscious disfluency characteristic of those who are temporarily upset, embarrassed, confused, or discombobulated does not have a word, so we’ll need to create. We’ll call this kind of disfluency bobulating. Almost everyone bobulates under certain stressful conditions. However, this is usually not a chronic problem, and even if it were, the person is generally unaware of his behavior and is, therefore, unlikely to have negative feelings toward it.

- The struggled, choked speech block that comes about when someone obstructs his air flow and constricts his muscles we’ll call blocking because the person is blocking something from his awareness (such uncomfortable emotions or self-perceptions) or blocking something from happening that may have negative repercussions. This is the chronic disfluency that most people think of when they speak of “stuttering” behavior that extends into adulthood. Unlike developmental disfluency and bobulating, blocking is a strategy designed to protect the speaker from unpleasant consequences.

- Finally, there is a fifth kind of dysfluency related to blocking that occurs when the person continues to repeat a word or syllable because he has a fear that he will block on the following word or syllable. Since he is just buying time until he feels ready to say the feared word, we’ll call this kind of dysfluency stalling. Because stalling is an alternate strategy to the overt struggle behavior associated with speech blocks, the two must be considered in the same vein.

Today, we’re looking at the blocking form of stuttering, which can be more accurately understood as a system involving the entire person. This system can be visualized as a six-sided figure—in effect, a Stuttering Hexagon—an interactive system that’s comprised of at least six essential components: behaviors emotions, perceptions, beliefs, intentions and physiological responses.

Each point of the Hexagon is connected to all the other points. Like a spider’s web, a jiggle anywhere is felt throughout the entire network. Everything affects, and is affected by, everything else. It is the moment-by-moment dynamic interaction of these six components that maintains the system’s homeostatic balance.

It is precisely because of the self-perpetuating nature of the system that it is so difficult to bring about permanent change at only one point. What usually happens is that after therapy most people who stutter slide back. This is because many therapy programs simply adopt a strategy of control in which only speech issues are addressed. Little is done to transform the system that supports the dysfluent speech.